Contents

The immune system: what is it?

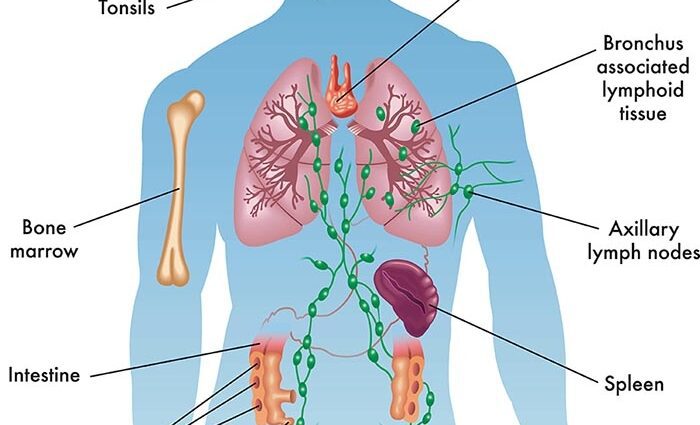

Organs of the immune system

Invisible to our eyes, it nevertheless provides security, day and night. Whether it is to cure an ear infection or cancer, the immune system is essential.

The immune system is made up of a system of complex interactions involving many different organs, cells and substances. The majority of cells are not found in the blood, but rather in a collection of organs called lymphoid organs.

- La bone marrow and thymus. These organs produce immune cells (lymphocytes).

- La rates, the lymph nodes, the tonsils and lymphoid cell clusters located on the mucous membranes of the digestive, respiratory, genital and urinary tracts. It is usually in these peripheral organs that the cells are called upon to respond.

The speed of action of the immune system is extremely important. This is based, among other things, on the efficiency of communication between the various players involved. The cardiovascular system is the only passageway that connects the lymphoid organs.

Although we cannot yet explain all the mechanisms, we now know that there are important interactions between the immune system, the nervous system and the endocrine system. Some secretions of immune cells are comparable to hormones secreted by the endocrine glands, and lymphoid organs have receptors for nerve and hormonal messages.

Stages of the immune response

The stages of the immune response can be divided into two:

- the nonspecific response, which constitutes “innate immunity” (so named because it is present from birth), acts without taking into account the nature of the micro-organism that it fights;

- the specific response, which confers “acquired immunity”, involves the recognition of the agent to be attacked and the memorization of this event.

The non-specific immune response

Physical barriers

La skin and mucous membranes are the first natural barriers that attackers come up against. The skin is the largest organ in the body and offers incredible protection against infections. In addition to constituting a physical interface between the environment and our vital systems, it offers an environment hostile to microbes: its surface is slightly acidic and rather dry, and it is covered with “good” bacteria. This explains why excessive hygiene is not necessarily a good thing for your health.

The mouth, eyes, ears, nose, urinary tract and genitals still provide passageways for germs. These routes also have their protection system. For example, coughing and sneezing reflexes push microorganisms out of the airways.

L’inflammation

Inflammation is the first barrier encountered by pathogenic microorganisms that cross our body envelope. Like the skin and mucous membranes, this type of immune response works without knowing the nature of the agent it is fighting. The purpose of inflammation is to inactivate the aggressors and to carry out tissue repair (in the event of injury). Here are the main stages of inflammation.

- La vasodilatation and the biggest permeability capillaries in the affected area have the effect of increasing the blood flow (responsible for the redness) and allowing the arrival of the actors of inflammation.

- Destruction of pathogens by phagocytes : a type of white blood cell that is able to take in pathogenic microorganisms or other diseased cells and destroy them. There are several types: monocytes, neutrophils, macrophages and natural killer cells (NK cells).

- The system of complement, which includes about twenty proteins that act in cascade and allow the direct destruction of microbes. The complement system can be activated by the microbes themselves or by the specific immune response (see below).

Interferons

In case of viral infection, the interferons are glycoproteins that inhibit the multiplication of viruses inside cells. Once secreted, they diffuse into the tissues and stimulate neighboring immune cells. The presence of microbial toxins can also trigger the production of interferons.

La fever is another defense mechanism sometimes present in the early stages of an infection. Its role is to accelerate immune reactions. At a temperature a little higher than normal, the cells act faster. In addition, germs reproduce less quickly. |

The specific immune response

This is where lymphocytes come in, a type of white blood cell of which two classes are distinguished: B lymphocytes and T lymphocytes.

- The lymphocytes B account for about 10% of lymphocytes circulating in the blood. When the immune system encounters a foreign agent, the B cells are stimulated, multiply and start to produce antibodies. Antibodies are proteins that attach themselves to foreign proteins; this is the starting point for the destruction of the pathogen.

- The T lymphocytes represent more than 80% of the lymphocytes in circulation. There are two types of T lymphocytes: cytotoxic T cells which, when activated, directly destroy cells infected with viruses and tumor cells, and facilitator T cells, which control other aspects of the immune response.

The specific immune response creates acquired immunity, one that develops over the years as a result of our body’s encounters with specific foreign molecules. Thus, our immune system remembers the particular bacteria and viruses that it has already encountered in order to make the second encounter much more efficient and faster. It is estimated that an adult has in memory 109 at 1011 different foreign proteins. This explains why one does not catch chickenpox and mononucleosis twice, for example. It is interesting to note that the effect of vaccination is to induce this memory of a first encounter with a pathogen.

Research and writing: Marie-Michèle Mantha, M.Sc. Medical review: Dr Paul Lépine, MDDO Text created on: 1er November 2004 |

Bibliography

Canadian Medical Association. Family Medical Encyclopedia, Selected from Reader’s Digest, Canada, 1993.

Starnbach MN (Ed). The truth about your immune system; what you need to know, President and Fellows of Harvard College, United States, 2004.

Vander Aj et al. Human physiology, Les Éditions de la Chenelière inc., Canada, 1995.