Contents

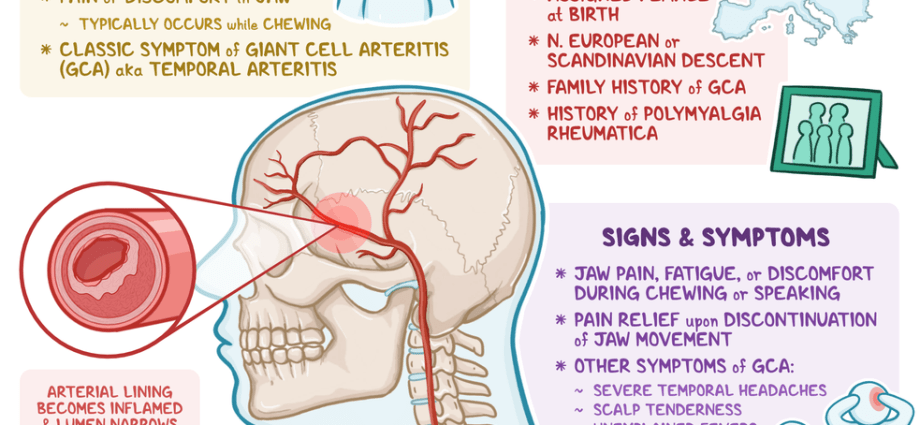

Giant cell arteritis is granulomatous vasculitis, mostly affecting the vessels of the head and neck. The causes of this condition are unknown, but environmental and genetic factors are taken into account. This type of inflammation usually occurs in older people after the age of 70, more often in women.

What is giant cell arteritis?

This ailment is granulomatous, chronic, systemic and primary vasculitis of low or high intensity, usually affecting the vessels of the head and neck. It especially concerns the temporal, ocular, vertebral arteries and the central retinal artery. Very often, in the course of giant cell arteritis, we can observe the coexistence of rheumatic polymyalgia (rheumatic disease from the group of systemic connective tissue diseases). Inflammation of the arteries is most common in the elderly, over 70 years of age, more often in women; the highest incidence is in the Scandinavian countries. The cause of the disease is not fully known, the role of the cellular immune response against the internal elastic lamina (membrane elastica interna) or smooth muscle cells of the vessel wall is postulated.

The causes of giant cell arteritis

Although the etiology of this ailment has not been fully elucidated, some factors are said to play a role:

- genetic,

- environmental,

- infectious.

The reasons for the familial occurrence of giant cell arteritis are confirmed by the fact that this inflammation is more common in Scandinavians and patients of Scandinavian origin living in other parts of the world (such as the United States). The disease can also occur as a reaction to infectious agents (i.e. viruses and fungi) in people with a genetic predisposition.

Giant cell arteritis may be related to the following pathogens:

- parwowirus B19,

- Parainfluenza type 1 virus,

- chlamydia,

- mycoplasma.

Do you want to take care of your circulatory system? Order Circulation – Doctor Life dietary supplement, which is designed to protect arteries against inflammation and take care of the proper functioning of the entire cardiovascular system.

Symptoms of giant cell arteritis

The aortic arch branches, usually branches of the external carotid artery, are involved in the course of the disease, but inflammation can also affect other arteries, e.g .:

- vertebral,

- temporal,

- posterior ciliary,

- outer cervical,

- internal jugular,

- ocular,

- middle retina.

It is very rare that the inflammation affects the iliac, brachial and femoral arteries. On the other hand, involvement of the abdominal aorta can be found autopsy.

Clinical symptoms:

- headaches (most often in the temporal or occipital area; they become active especially at night and prevent the patient from falling asleep),

- visual disturbances up to and including loss of vision (patients often suffer from double vision and temporary amblyopia); visual acuity disorders; inflammation of the orbital tissues,

- pressure sensitivity over a thickened and pulseless temporal artery that is visible and twisted,

- dysphagia,

- claudication of the jaw and tongue (a symptom occurring in half of the patients); the cause is ischemia of the masseter muscles; may involve the tongue, causing painful ulcers or the muscles involved in the swallowing process,

- low-grade fever or fever, which can be as high as 40 degrees Celsius,

- weakness,

- weight loss

- lack of appetite

- eye pain,

- muscle aches,

- symptoms of the coronary arteries and the aortic arch,

- symptoms of rheumatic polymyalgia concerning the muscles of the shoulder and hip belt.

Diagnosis of giant cell arteritis

There are three types of examinations in the diagnosis of ailments.

1. Imaging studies – they include: Doppler ultrasound, arteriography, CT, MR, PET. These studies show the features of vascular wall inflammation) or various complications, e.g. aneurysms, aortic dissection, occlusion of the involved arteries.

2. Laboratory research – ESR often above 100, presence of acute phase proteins, leukocytosis, pANCA antibodies are rare.

3. Temporal artery biopsy – shows fibrinous necrosis accompanied by granulomatous inflammation of the vessel wall with the presence of giant cells that may contain fragments of internally damaged elastic membrane.

The doctor makes a diagnosis based on the above-mentioned clinical symptoms together with the results of the above-mentioned tests. There are certain criteria that help to differentiate giant cell arteritis from other conditions:

- age over 50,

- OB value above 50 mm / h,

- Headache,

- positive artery biopsy,

- soreness due to compression of the temporal artery,

- weak pulse of the temporal artery under pressure.

Giant cell arteritis should be differentiated from other systemic vasculitis, headache of a different origin, atherosclerosis, glaucoma attack, polyangiitis nodosa, granulomatosis associated with polyangiitis, and Taksayasu’s disease.

Giant cell arteritis treatment

The treatment is generally steroids (starting doses of prednisone 60-80 mg / day; after remission 10-20 mg / day). The appearance of eye symptoms in the patient is an indication for the administration of IV methylprednisolone in a dose of 500–1000 mg for 3 consecutive days. In relapses, it is generally sufficient to increase the dose, unless ocular or neurological symptoms develop. Some patients with giant cell arteritis experience relapses, which are an indication for corticotherapy for up to several years.

For the prevention of blindness and stroke, patients are advised to take acetylsalicylic acid.

Can giant cell arteritis lead to complications?

A few years after the diagnosis is made, aneurysms that like to burst may appear. In addition, aortic dissection may occur. In patients whose disease affects the ophthalmic arteries, there is a possibility of blindness, often bilateral (50% of cases).

The prognosis of the disease is good as it is rarely fatal. Therapy with corticosteroids causes remission of symptoms and alleviates pain. Additionally, it prevents eye complications.

Lit .: [1] Stegman C.A., Kallenberg C.G.M.: Clinical aspects of primary vasculitis. Springer Semin Immunopathol 2001, 23; 231-51. [2] Janette J.C., Falk R.J., Andrassy K. i wsp.: Nomenclature of systemic vasculitis. Proposal of an Internal Consensus Conference. Arthritis Rheum 1994, 37; 187-92. [3] Małdyk H.: Zapalenia naczyń. Pol Arch Med Wew 1994, 91; 395-401.

Source: A. Kaszuba, Z. Adamski: “Lexicon of dermatology”; XNUMXst edition, Czelej Publishing House