Do you know what the cost of a hamburger is? If you say it’s $2.50 or the current price at a McDonald’s restaurant, you’re vastly underestimating its real price. The price tag does not reflect the true cost of production. Each hamburger is the suffering of an animal, the cost of treating a person who eats it, and economic and environmental problems.

Unfortunately, it is difficult to give a realistic estimate of the cost of a hamburger, because most of the operating costs are hidden from view or simply ignored. Most people do not see the pain of animals because they lived on farms, and then they were castrated and killed. Yet most people are well aware of the hormones and drugs fed or directly administered to animals. And in doing so, they understand that high rates of chemical use can pose a threat to people due to the emergence of antibiotic-resistant microbes.

There is growing awareness of the price we pay for hamburgers with our health, that we increase the risks of heart attacks, colon cancer, and high blood pressure. But a full-scale study of the health risks of eating meat is far from complete.

But the costs involved in research pale in comparison to the environmental cost of livestock production. No other human activity has led to such a massive destruction of much of the landscape and perhaps the world landscape as our “love” for the cow and its meat.

If the real cost of a hamburger could be even approximately estimated at a minimum, then it would turn out that every hamburger is really priceless. How would you rate polluted water bodies? How would you rate the daily disappearing species? How do you figure out the real cost of topsoil degradation? These losses are almost impossible to estimate, but they are the real value of livestock products.

This is your land, this is our land…

Nowhere has the cost of livestock production become more evident than in the lands of the West. The American West is a grandiose landscape. Arid, rocky and barren landscape. Deserts are defined as regions with minimal rainfall and high evaporation rates—in other words, they are characterized by minimal rainfall and sparse vegetation.

In the West, it takes a lot of land to raise one cow to provide enough fodder. For example, a couple of acres of land to raise a cow is enough in a humid climate like Georgia, but in the arid and mountainous areas of the West, you may need 200-300 hectares to support a cow. Unfortunately, the intensive fodder cultivation that supports the livestock business is causing irreparable damage to nature and the ecological processes of the Earth.

Brittle soils and plant communities are destroyed. And therein lies the problem. It is an environmental crime to economically support livestock farming, no matter what livestock advocates say.

Environmentally Unsustainable – Economically Unsustainable

Some may ask how pastoralism has survived for so many generations if it is destroying the West? It’s not easy to answer. First, pastoralism will not survive – it has been in decline for decades. The land simply cannot support so many livestock, the overall productivity of the western lands has declined due to livestock rearing. And many of the ranchers changed jobs and moved to the city.

However, pastoralism survives mainly on huge subsidies, both economic and environmental. The Western farmer today has a chance to compete in the world market only thanks to state subsidies. Taxpayers pay for things like predator control, weed control, livestock disease control, drought mitigation, expensive irrigation systems that benefit livestock farmers.

There are other subsidies that are more subtle and less visible, such as providing services to sparsely populated ranches. Taxpayers are forced to subsidize ranchers by providing them with protection, mail, school buses, road repairs, and other public services that often exceed the tax contributions of these landowners – in large part because farmland is often taxed at preferential rates, that is, they pay significantly less compared to others.

Other subsidies are difficult to assess, as many financial aid programs are hidden in several ways. For example, when the US Forest Service puts up fences to keep cows out of the forest, the cost of the work is deducted from the budget, even though there would be no need for the fence in the absence of cows. Or take all those miles of fencing along the western highway to the right of the tracks meant to keep cows out of the highway.

Who do you think pays for this? Not a ranch. The annual subsidy allocated to the welfare of farmers who farm on public lands and make up less than 1% of all livestock producers is at least $500 million. If we realized that this money is being charged from us, we would understand that we pay very dearly for hamburgers, even if we do not buy them.

We are paying for some Western farmers to have access to public land – our land, and in many cases the most fragile soils and the most diverse plant life.

Soil destruction subsidy

Virtually every acre of land that can be used for livestock grazing is leased by the federal government to a handful of farmers, representing about 1% of all livestock producers. These men (and a few women) are allowed to graze their animals on these lands for next to nothing, especially considering the environmental impact.

Livestock compacts the top layer of soil with their hooves, reducing the penetration of water into the ground and its moisture content. Animal husbandry causes livestock to infect wild animals, which leads to their local extinction. Animal husbandry destroys natural vegetation and tramples spring water sources, pollutes water bodies, destroying the habitat of fish and many other creatures. Indeed, farm animals are a major factor in the destruction of green areas along coasts known as coastal habitats.

And since more than 70-75% of the West’s wildlife species depend to some extent on coastal habitat, the impact of livestock in coastal habitat destruction cannot but be appalling. And it’s not a minor impact. Approximately 300 million acres of US public land is leased to livestock farmers!

desert ranch

Livestock is also one of the largest consumers of water in the West. Massive irrigation is needed to produce feed for livestock. Even in California, where the vast majority of the country’s vegetables and fruits are grown, irrigated farmland that grows livestock feed holds the palm in terms of the amount of land occupied.

The vast majority of developed water resources (reservoirs), especially in the West, are used for the needs of irrigated agriculture, primarily for growing fodder crops. Indeed, in the 17 western states, irrigation accounts for an average of 82% of all water withdrawals, 96% in Montana, and 21% in North Dakota. This is known to contribute to the extinction of aquatic species from snails to trout.

But economic subsidies pale in comparison to environmental subsidies. Livestock may well be the largest land user in the United States. In addition to the 300 million acres of public land that grazes domestic animals, there are 400 million acres of private pastures across the country used for grazing. In addition, hundreds of millions of acres of farmland are used to produce feed for livestock.

Last year, for example, more than 80 million hectares of corn were planted in the United States – and most of the crop will go to feed livestock. Similarly, most of the soybean, rapeseed, alfalfa and other crops are destined for fattening livestock. In fact, most of our farmland is not used to grow human food, but to produce livestock feed. This means that hundreds of millions of acres of land and water are polluted with pesticides and other chemicals for the sake of a hamburger, and many acres of soil are depleted.

This development and change of the natural landscape is not uniform, however, agriculture has not only contributed to a significant loss of species, but has almost completely destroyed some ecosystems. For example, 77 percent of Iowa is now arable, and 62 percent in North Dakota and 59 percent in Kansas. Thus, most of the prairies lost high and medium vegetation.

In general, approximately 70-75% of the land area of the United States (excluding Alaska) is used for livestock production in one form or another – for growing fodder crops, for farm pasture or grazing livestock. The ecological footprint of this industry is huge.

Solutions: immediate and long-term

In fact, we need a surprisingly small amount of land to feed ourselves. All vegetables grown in the United States occupy a little over three million hectares of land. Fruit and nuts occupy another five million acres. Potatoes and grains are grown on 60 million hectares of land, but more than XNUMX percent of the grains, including oats, wheat, barley and other crops, are fed to livestock.

Obviously, if meat were excluded from our diet, there would be no shift towards increasing the need for grains and vegetable products. However, given the inefficiency of converting grain into the meat of large animals, particularly cows, any increase in acres dedicated to growing grain and vegetables will easily be counterbalanced by a significant decrease in the number of acres used for animal husbandry.

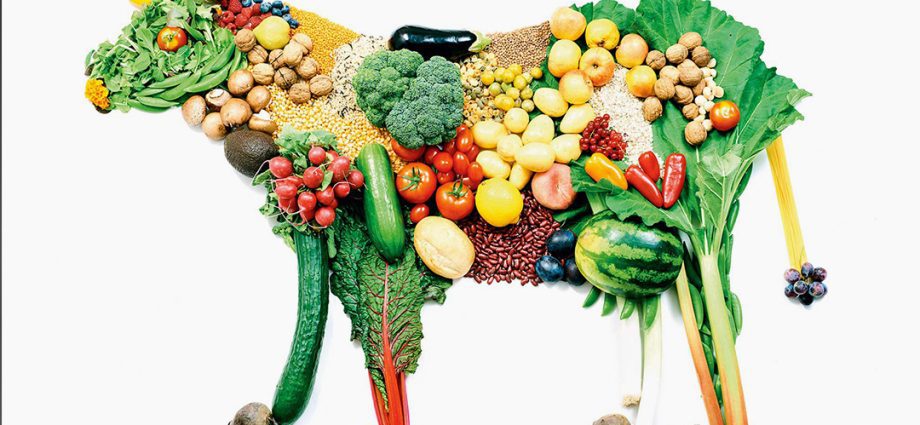

We already know that a vegetarian diet is not only better for people, but for the earth as well. There are numerous obvious solutions. Plant-based nutrition is one of the most important steps anyone can take to promote a healthy planet.

In the absence of a large-scale population transition from a meat-based diet to a vegetarian diet, there are still options that could contribute to changing the way Americans eat and use land. The National Wildlife Refuge is campaigning to reduce livestock production on public lands, and they are talking about the need to subsidize ranchers on public lands for not raising and grazing livestock. While the American people are not obligated to allow cattle grazing on any of their lands, the political reality is that pastoralism will not be banned, despite all the damage it causes.

This proposal is politically environmentally responsible. This will result in the release of up to 300 million hectares of land from grazing – an area three times the size of California. However, the removal of livestock from state lands will not lead to significant reductions in meat production, because only a small percentage of livestock is produced in the country on state lands. And once people see the benefits of reducing the number of cows, the reduction of their breeding on private land in the West (and elsewhere) is likely to be realized.

Free land

What are we going to do with all these cow-free acres? Imagine the West without fences, herds of bison, elk, antelopes and rams. Imagine rivers, transparent and clean. Imagine wolves reclaiming much of the West. Such a miracle is possible, but only if we free most of the West from cattle. Fortunately, such a future is possible on public lands.