The path to personal well-being is through compassion for others. What you hear about in a Sunday school or a lecture on Buddhism has now been scientifically proven and can be considered a scientifically recommended way to become happier. Psychology professor Susan Krauss Whitborn talks more about this.

The desire to help others can take many forms. In some cases, indifference to a stranger is already help. You can push away the thought “let someone else do it” and reach out to a passerby who stumbles on the sidewalk. Help orient someone who looks lost. Tell a person passing by that his sneaker is untied. All those small actions matter, says University of Massachusetts psychology professor Susan Krauss Whitbourne.

When it comes to friends and relatives, our help can be invaluable for them. For example, a brother has a hard time at work, and we find time to meet for a cup of coffee to let him talk and advise something. A neighbor enters the entrance with heavy bags, and we help her carry food to the apartment.

For some, it’s all part of the job. Store employees are paid to help shoppers find the right products. The task of physicians and psychotherapists is to relieve pain, both physical and mental. The ability to listen and then do something to help those in need is perhaps one of the most important parts of their job, although sometimes quite burdensome.

Compassion vs empathy

Researchers tend to study empathy and altruism rather than compassion itself. Aino Saarinen and colleagues at the University of Oulu in Finland point out that, unlike empathy, which involves the ability to understand and share the positive and negative feelings of others, compassion means “concern for the suffering of others and the desire to alleviate it.”

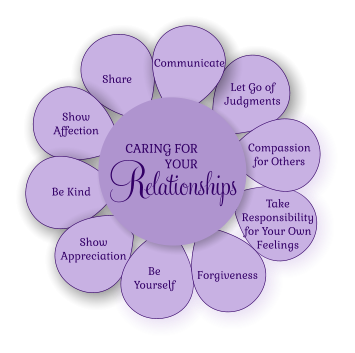

Proponents of positive psychology have long assumed that the predisposition to compassion should contribute to human well-being, but this area has remained relatively understudied. However, Finnish scientists argue that there is definitely a connection between qualities like compassion and higher life satisfaction, happiness and good mood. Compassion-like qualities are kindness, empathy, altruism, prosociality, and self-compassion or self-acceptance.

Previous research on compassion and its related qualities has uncovered certain paradoxes. For example, a person who is overly empathic and altruistic is at greater risk of developing depression because «the practice of empathy for the suffering of others increases stress levels and affects the person negatively, while the practice of compassion affects him positively.»

Imagine that the counselor who answered the call, along with you, began to get angry or upset because of how terrible this situation is.

In other words, when we feel the pain of others but do nothing to alleviate it, we focus on the negative aspects of our own experience and may feel powerless, while compassion means that we are helping, and not just passively watching the suffering of others.

Susan Whitburn suggests recalling a situation when we contacted the support service — for example, our Internet provider. Connection problems at the most inopportune moment can thoroughly piss you off. “Imagine that the counselor who answered the phone, along with you, became angry or upset because of how dire this situation is. It is unlikely that he will be able to help you solve the problem. However, this is unlikely to happen: most likely, he will ask questions to diagnose the problem and suggest options for solving it. When the connection can be established, your well-being will improve, and, most likely, he will feel better, because he will experience the satisfaction of a job well done.

Long term research

Saarinen and colleagues have studied the relationship between compassion and well-being in depth. Specifically, they used data from a national study that began in 1980 with 3596 young Finns born between 1962 and 1972.

Testing within the framework of the experiment was carried out three times: in 1997, 2001 and 2012. By the time of the final testing in 2012, the age of the program participants was in the range from 35 to 50 years. Long-term follow-up allowed the scientists to track changes in the level of compassion and measures of participants’ sense of well-being.

To measure compassion, Saarinen and colleagues used a complex system of questions and statements, the answers to which were further systematized and analyzed. For example: “I enjoy seeing my enemies suffer”, “I enjoy helping others even if they mistreated me”, and “I hate to see someone suffer”.

Compassionate people get more social support because they maintain more positive communication patterns.

Measures of emotional well-being included a scale of statements such as: «In general, I feel happy», «I have fewer fears than other people my age.» A separate cognitive well-being scale took into account perceived social support (“When I need help, my friends always provide it”), life satisfaction (“How satisfied are you with your life?”), subjective health (“How is your health compared to peers?”), and optimism (“In ambiguous situations, I think that everything will be resolved in the best way”).

Over the years of the study, some of the participants have changed — unfortunately, this inevitably happens with such long-term projects. Those who made it to the finals were predominantly those who were older at the start of the project, had not dropped out of school, and came from educated families of a higher social class.

Key to well-being

As predicted, people with higher levels of compassion maintained higher levels of affective and cognitive well-being, overall life satisfaction, optimism, and social support. Even subjective assessments of the health status of such people were higher. These results suggest that listening and being helpful are key factors in maintaining personal well-being.

During the experiment, the researchers noted that compassionate people themselves, in turn, received more social support, because they “maintained more positive communication patterns. Think about the people you feel good around. Most likely, they know how to listen sympathetically and then try to help, and they also do not seem to harbor hostility even towards unpleasant people. You might not want to befriend a sympathetic support person, but you certainly wouldn’t mind getting their help the next time you’re in trouble.»

“The capacity for compassion provides us with key psychological benefits, which include not only improved mood, health, and self-esteem, but also an expanded and strengthened network of friends and supporters,” sums up Susan Whitbourne. In other words, scientists nevertheless proved scientifically what philosophers have been writing about for a long time and what supporters of many religions preach: compassion for others makes us happier.

About the Author: Susan Krauss Whitborn is a professor of psychology at the University of Massachusetts and the author of 16 books on psychology.