Contents

Atherogenic: definition, risks, prevention

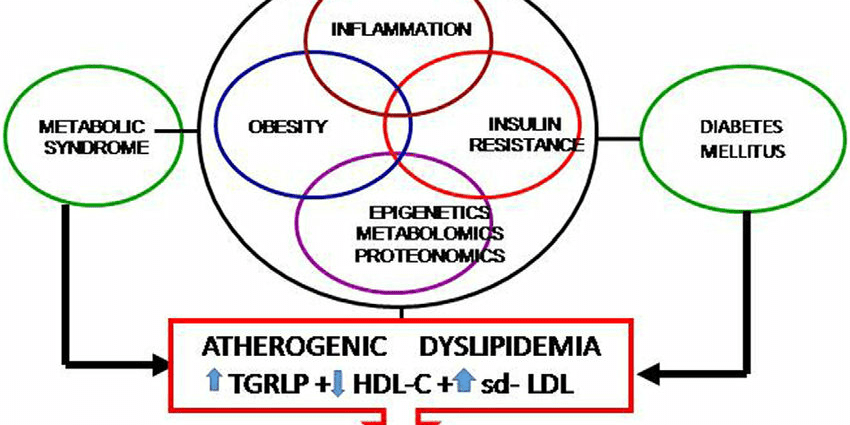

The term “atherogenic” refers to substances or factors capable of producing an atheroma, or deposit of plaques made up of LDL-cholesterol, inflammatory cells and a fibrous shell. This phenomenon is particularly dangerous if the artery supplies a vital organ such as the heart or the brain. It is the cause of most cardiovascular diseases, including stroke and myocardial infarction. Its primary prevention consists of adopting better hygienic and dietary habits. Secondary prevention is offered to patients who already have symptoms or a complication. In this case, the objective is to reduce the risk of a new complication, on the same territory or on another vascular territory.

What does the term atherogenic mean?

The term “atherogenic” refers to substances or factors capable of producing an atheroma, that is to say a deposit of plaques made up of lipids, inflammatory cells, smooth muscle cells and connective tissue. These plaques attach themselves to the internal walls of medium and large arteries, in particular those of the heart, brain and legs, and lead to a local modification of the appearance and nature of these walls.

The deposition of these plaques can lead to serious complications such as coronary artery disease by causing:

- thickening and loss of elasticity of the arterial wall (atherosclerosis);

- a decrease in the diameter of the artery (stenosis). This phenomenon can reach more than 70% of the diameter of the artery. This is called tight stenosis;

- partial or total blockage of the artery (thrombosis).

We speak of an atherogenic diet to designate a diet rich in fat, such as the Western diet which is particularly rich in saturated fat and trans fatty acids following the hydrogenation of fatty acids by industrial processing.

What are the causes of the formation of atheromatous plaques?

The development of atheromatous plaques can be due to several factors, but the main cause is excess cholesterol in the blood, or hypercholesterolemia. Indeed, the creation of atheromatous plaque depends on the balance between dietary intake of cholesterol, its circulating level and its elimination.

Over the course of life, a number of mechanisms will first create breaches in the arterial wall, in particular in the bifurcation areas:

- arterial hypertension which, in addition to its mechanical action on the wall, modifies the intracellular flow of lipoproteins;

- vasomotor substances, such as angiotensin and catecholamines, which manage to expose the sub-endothelial collagen;

- hypoxiant substances, such as nicotine, which cause cellular distress leading to the spreading of intercellular junctions.

These breaches will allow the passage into the arterial wall of small lipoproteins such as HDL (High Density Lipoprotein) and LDL (Low Density Lipoprotein) lipoproteins. LDL-cholesterol, often referred to as “bad cholesterol”, present in the bloodstream can build up. It thus creates the first early lesions, called lipid streaks. These are deposits that form raised lipid trails on the inner wall of the artery. Little by little, the LDL-cholesterol oxidizes there and becomes inflammatory for the internal wall. In order to eliminate it, the latter recruits macrophages which are gorged with LDL-cholesterol. Apart from any regulatory mechanism, macrophages become bulky, die by apoptosis while remaining locally trapped. The normal systems of elimination of cellular debris not being able to intervene, they accumulate in the atheroma plaque which grows gradually. In response to this mechanism, the smooth muscle cells of the vascular wall migrate into the plaque in an attempt to isolate this inflammatory cell cluster. They will form a fibrous screed made up of collagen fibers: the whole forms a more or less rigid and stable plate. Under certain conditions, plaque macrophages produce proteases capable of digesting collagen produced by smooth muscle cells. When this inflammatory phenomenon becomes chronic, the action of proteases on the fibers promotes the refinement of the screed which becomes more fragile and can rupture. In this case, the inner wall of the artery may crack. Blood platelets aggregate with cellular debris and lipids accumulated in the plaque to form a clot, which will slow down and then block blood flow.

The flow of cholesterol in the body is provided by LDL and HDL lipoproteins which carry cholesterol, from food in the blood, from the intestine to the liver or arteries, or from the arteries to the liver. This is why, when we want to assess the atherogenic risk, we dose these lipoproteins and compare their quantities:

- If there are lots of LDL lipoproteins, which carry cholesterol to the arteries, the risk is high. This is why LDL-cholesterol is called atherogenic;

- This risk is reduced when the blood level of HDL lipoproteins, which ensure the return of cholesterol to the liver where it is processed before being eliminated, is high. Thus, HDL-HDL-cholesterol is qualified as cardioprotective when its level is high, and as a cardiovascular risk factor when its level is low.

What are the symptoms resulting from the formation of atheromatous plaques?

The thickening of atheromatous plaques can gradually interfere with blood flow and lead to the appearance of localized symptoms:

- pain;

- dizziness;

- shortness of breath;

- instability when walking, etc.

The serious complications of atherosclerosis arise from the rupture of atherosclerotic plaques, resulting in the formation of a clot or thrombus, which blocks blood flow and causes ischemia, the consequences of which can be serious or fatal. The arteries of different organs can be affected:

- coronary artery disease, in the heart, with angina or angina pectoris as a symptom, and a risk of myocardial infarction;

- carotids, in the neck, with a risk of cerebrovascular accident (stroke);

- the abdominal aorta, under the diaphragm, with a risk of aneurysm rupture;

- the digestive arteries, in the intestine, with a risk of mesenteric infarction;

- the renal arteries, at the level of the kidney, with a risk of renal infarction;

- the arteries of the lower limbs with a symptom of limping of the lower limbs.

How to prevent and fight against the formation of atherosclerotic plaques?

Apart from heredity, sex and age, the prevention of the formation of atheromatous plaques relies on the correction of cardiovascular risk factors:

- weight control, high blood pressure and diabetes;

- smoking cessation;

- regular physical activity;

- adoption of healthy eating habits;

- limitation of alcohol consumption;

- stress management, etc.

When the atheromatous plaque is insignificant and has not resulted in an impact, this primary prevention may be sufficient. If these first measures fail, when the plaque has evolved, drug treatment may be recommended. It can also be prescribed straight away if there is a high risk of complications. It is systematically recommended for secondary prevention after a first cardiovascular event. This drug treatment includes:

- antiplatelet drugs, such as aspirin in small doses, to thin the blood;

- lipid-lowering drugs (statins, fibrates, ezetimibe, cholestyramine, alone or in combination) with the objectives of reducing bad cholesterol levels, normalizing cholesterol levels and stabilizing atheromatous plaques.

Faced with advanced atheromatous plaques with tight stenosis, revascularization by coronary angioplasty may be considered. This allows to dilate the atheromatous zone thanks to an inflated balloon on-site in the artery with ischemia. In order to maintain the opening and restore blood flow, a small mechanical device called a stent is installed and left in place.