Today we cut our hair for the sake of a new hairstyle, and once people were afraid to do it, because they believed that they would harm the whole body. The cut hair was protected, hidden, and sometimes they were sacrificed to the gods for sins …

In the modern world, we treat our hairstyles much easier than a few centuries ago, and are not afraid of scissors. Although, maybe in vain? After all, there are people who are ready to pay a lot of money for strands of outstanding personalities, believing that they carry the spirit of a person.

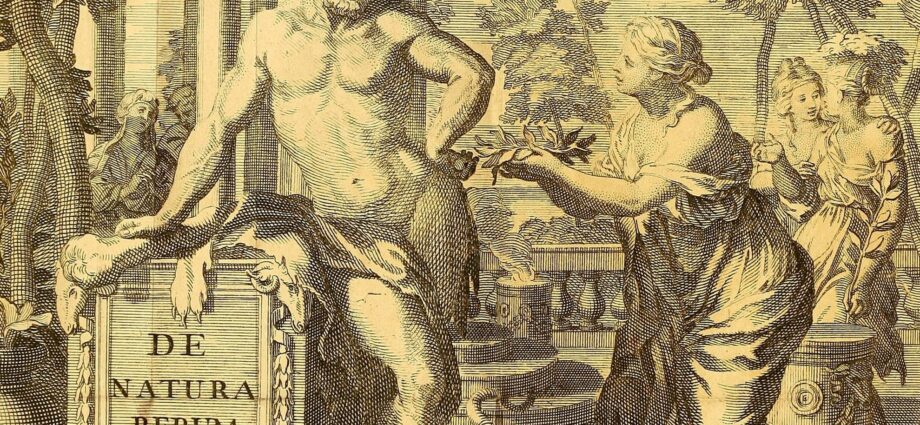

About what forces are hidden in hair, why they made rings, pendants and paintings from them, in his book “Hair. World history “told the professor Kurt Stenn… He has been studying hair for over 30 years! The editorial staff of Wday.ru publishes an excerpt from the scientist’s book.

On October 25, 2007, Heritage Auction Gallery in Dallas sold a lock of black hair cut from Che Guevara’s head. Auction participant Bill Butler, a bookseller, paid an incredible price for the relic – $ 119500 (8,8 million rubles). Butler said he wanted to add a bit of a revolutionary leader to his 1960s souvenir collection. In the same year, just a little earlier, this auction house sold a lock of President Abraham Lincoln’s hair for $ 11095 (818 thousand rubles) and a lock of hair of Confederate General Jeb Stewart for 44812 (3,3 million rubles).

The hair of famous people is highly prized. But why? For collectors, hair carries the spirit of the person to whom it belonged. Having received these strands at their disposal, collectors acquire a piece of this person. In many cultures, both past and present, it is believed that hair harbors the vitality of its owner.

In mythology and culture, there are references to spirits that live in the hair, connected to the body or separated from it. For example, in Greek mythology of Mnemosyne, mother of nine muses, kept memories in her very long hair. In the Bible, Samson’s strength was not in the muscles, but in the hair, so when his mistress cut them off, he lost all his strength and regained it only after the hair grew back.

In many cultures, both past and present, it is believed that hair harbors the vitality of its owner. In Japanese tradition, strength sumo wrestler is in his hair. As a sign of the end of his sports career, during the ceremony of retirement from this sport, the sumo wrestler has his hair cut off.

Many believed that the essence of a person is related to his hair. It was widely believed that any damage to the hair, even when cut, could harm the body. That is why representatives West African Yoruba protect their cut hair so that the spirit dwelling in it does not fall under the influence of a villain who can exploit it.

In the folklore of many peoples, there are stories of sorcerers or sorceresses who applied a decoction of love to their hair in order to seduce a person. Hair was also sacrificed to the gods. Japanese women donated strands of their hair to the temple so that their beloved would return home unharmed, and modern indian women give their hair to the temple to atone for sins.

A strand of the deceased as a decoration

People have kept their hair as a souvenir or a religious relic for a long time, but this tradition became especially popular during the Civil War in England after the execution of the king. Charles I… The people who supported the king wore locks of the executed monarch’s hair in jewelry as a sign of mourning and as a declaration of their political predilections. Soon the tradition spread throughout the kingdom, and many began to wear similar jewelry as a sign of mourning for the deceased loved ones.

These decorations – memento mori (Latin expression meaning “remember death”) – usually represented by a gold medallion on a black velvet ribbon. The medallion was shaped like one of the symbols of death. For example, it could be a coffin, skeleton, hourglass, or gravedigger’s spade. The name of the deceased was engraved in the center of the medallion. A lock of hair was placed inside the medallion.

One of the most famous supporters of the memento mori tradition was the English Queen Victoria… She was happily married, which is very unusual for monarchs. Her husband, Prince Consort Albert, Duke of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha, was well educated. An innovator, a progressive scientist, he was an irreplaceable adviser to the Queen. When he died in 1861, Victoria plunged into a long and deep mourning. Although she was never able to fully recover from the loss, the Queen found some comfort in retaining the strands of Albert’s hair, which she wore in medallions, pendants, and rings.

Perhaps inspired by the example of Queen Victoria, American women in the XNUMXth century appreciated the spiritual properties of hair. They used cut strands of hair as a symbol of friendship, love, mourning, and family ties. The hair of loved ones remained with them all the time in everyday life thanks to jewelry. Strands of hair were framed under glass and hung on the wall, and stored in scrapbooks on a desk or shelf.

Martha Washington, a great lover of such jewelry, cut off strands of hair from guests and placed them in a medallion or under glass. Have Abigail Adams, wife of the second President of the United States, John Adams, had a brooch and pin that contained her own hair, the hair of her husband and son, John Quincy Adams, the sixth President of the United States. Victorian poet Robert Browning wore a gold ring with intertwined locks of hair of himself and his wife. The ring was engraved with the inscription “Ba” and the words “God bless you, June 29, 1861”. On this day, his wife, Elizabeth Barrett Browning, died.

Hair exchange could sometimes mean a marriage proposal

But strands of hair have long symbolized more than just friendship, family ties, or mourning. Hair exchange was of particular importance in a romantic relationship… In some cases, when a shy young man asked a girl for a lock of hair, it was the beginning of a marriage proposal. But some ladies’ men, who had no idea of getting married, kept locks of hair as symbols of their victories.

Women used hair as seduction tool… Lady Caroline Lam advertised her flaming and fading connection with Lord Byron by sending him a lock of her pubic hair in a gold medallion with a miniature portrait of Byron. History has not kept track of what he did with the gift, but we do know that Byron ended his relationship with Caroline shortly thereafter.

As the relationship progressed, the man or woman proudly kept each other’s hair. But as soon as the passions subsided, the donated hair took on a different aspect. Remember the poem Burial, written in 1633 by the British poet John Donne. In this poem, the rejected lover asks those who will prepare his body for the funeral not to ask unnecessary questions and not to touch the talisman from a strand of hair worn on his arm. This strand of hair was donated by a woman who now rejects it. In the last line, the hero adds gloomily: “You did not save me, / For this, I bury a part of you.” For a rejected lover, this hair is more than a symbol of his love. This is the real part of the woman, and he takes revenge on her.

To create such souvenirs, people most often took a lock of hair (their own, a deceased or a living person to whom they had a special affection), dipped it in boiling water, dried it, and then shaped it or skillfully tied it. In some cases, the hair was powdered, mixed with glue, and used as a dye for fashion ornaments. Strands of hair were put into letters and albums, creating complex compositions, adding an expression of their love in the form of poems, essays and drawings.

Using hair as a souvenir began as a worthless gesture that anyone could afford. But in the end, this art became the domain of the middle class, who had free time to develop these skills, and close friends with whom they could share this art.

In the middle of the XNUMXth century, the demand for hair crafts grew to such an extent that many women turned to artists for help. The emergence of professionals in the field has made the art more accessible and the messages less personal and more commercial. But such souvenirs did not become cheaper. Those who bought professionally made hair jewelry were expensive.

In the 1855 issue of Godey’s Magazine and Lady’s Book, you see advertisements for mourning necklaces priced between $ 4 and $ 7 each. And this at a time when the average per capita personal wealth in the United States was just over $ 300. By the end of the XNUMXth century, interest in hair jewelry had faded, partly because women had other options for expressing their feelings, and partly because photography, a new way to preserve their image, was emerging. By the beginning of the XNUMXth century, memento mori were completely out of fashion, considered dark, sentimental and simply out of date.

The largest collection of hair jewelry from this period is located in Independence, Missouri, in a simple one-story brick building. The Hair Museum has three large rooms. The exhibits hang on the walls or are displayed in large display cabinets. Museum founder Leila Kone, a former salon owner and hairdresser-stylist, began collecting hair pieces over 60 years ago when she saw a framed hair wreath in an antique shop window on her way to a shoe store. The money earmarked to buy shoes – $ 135 – was spent on the purchase of a hair composition. Cone continued to collect the collection, purchasing hair pieces on every occasion: at antiques sales, at auctions, at garage sales and on a tip.

In the collection of Leila Kone there are sculptures of hair and many different ornaments in which hair is inserted. These are watches, earrings, medallions, pendants, rings, brooches and pins. The largest exhibits are hair wreath compositions.

The most typical example is Cone’s first purchase. This is a composition, enclosed in a golden frame, of blond hair, braided and styled in the form of a horseshoe, and strands in the form of leaves, which in places cover this horseshoe. It should have been hung on the wall. The inscription “From mom and dad” has been preserved on the back. Such compositions were very popular. As a rule, each family member gave one “sheet” made of his hair, and then the artist wrote next to such a “sheet” the name of the person and his family ties. It turned out to be a kind of family tree. After all family members contributed to this creation, the artist closed the circle to complete the wreath.

In recent years, a new generation of sculptors have begun to use hair as a medium of expression, far from the memento mori of the past. Most people are comfortable with animal hair used in a work of art, but human hair has become an integral part of artistic creation. Unlike paper, wood, paint, clay, stone, bronze, metal and plastic, human hair is a “product” of a living, thinking, laughing and crying human body. Therefore, the use of hair as a material raises the question: who gave their hair and why?

Hair is used in different ways in art. One of the basic methods is demonstrated by the artist Althea Murphy-Price, who creates voluminous compositions from hair. Terry Boddy took the idea somewhat literally that hair can “speak” and created words in which letters are made from hair. In Babs Reingold’s The Question of Beauty, a faded photograph of a child is juxtaposed with a golden lock of the same child’s hair, accentuating the contrast between the impermanence of life and the eternity of hair. In Untitled 1990, Tom Friedman introduced his pubic hair, sealed in a plain white bar of soap. And artist Sania Clarke weaved African hair into the fabric of the Confederate flag and home chair, highlighting the presence of Africans in the fabric of society at the time.

The work of Althea Murphy-Price

The work of Althea Murphy-Price

These are just a few of the many artworks that use human hair as their material. Exploiting this highly personal material (perhaps one of the most intimate parts of the body), these artists make powerful statements with philosophical, social, political and moral overtones. Their creations and memento mori show that hair detached from the body can send signals as powerful as body hair. Throughout human history, people have been interested in the nature of hair and what signals it gives.