About the Author: Vasily Radaev, Foodsharing volunteer I will give away food.

In the Cambridge Dictionary, the term food sharing defined as sharing meals with other people, sharing space for growing, preparing and eating food, sharing culinary interests, and talking about food. Remember grandma asking about your last meal? So, you were engaged in food sharing.

Food-sharing projects make cities’ food systems more sustainable: it’s nice to have an urban vegetable garden in your neighborhood and know that the nearest supermarket doesn’t waste tens of kilos of food every day.

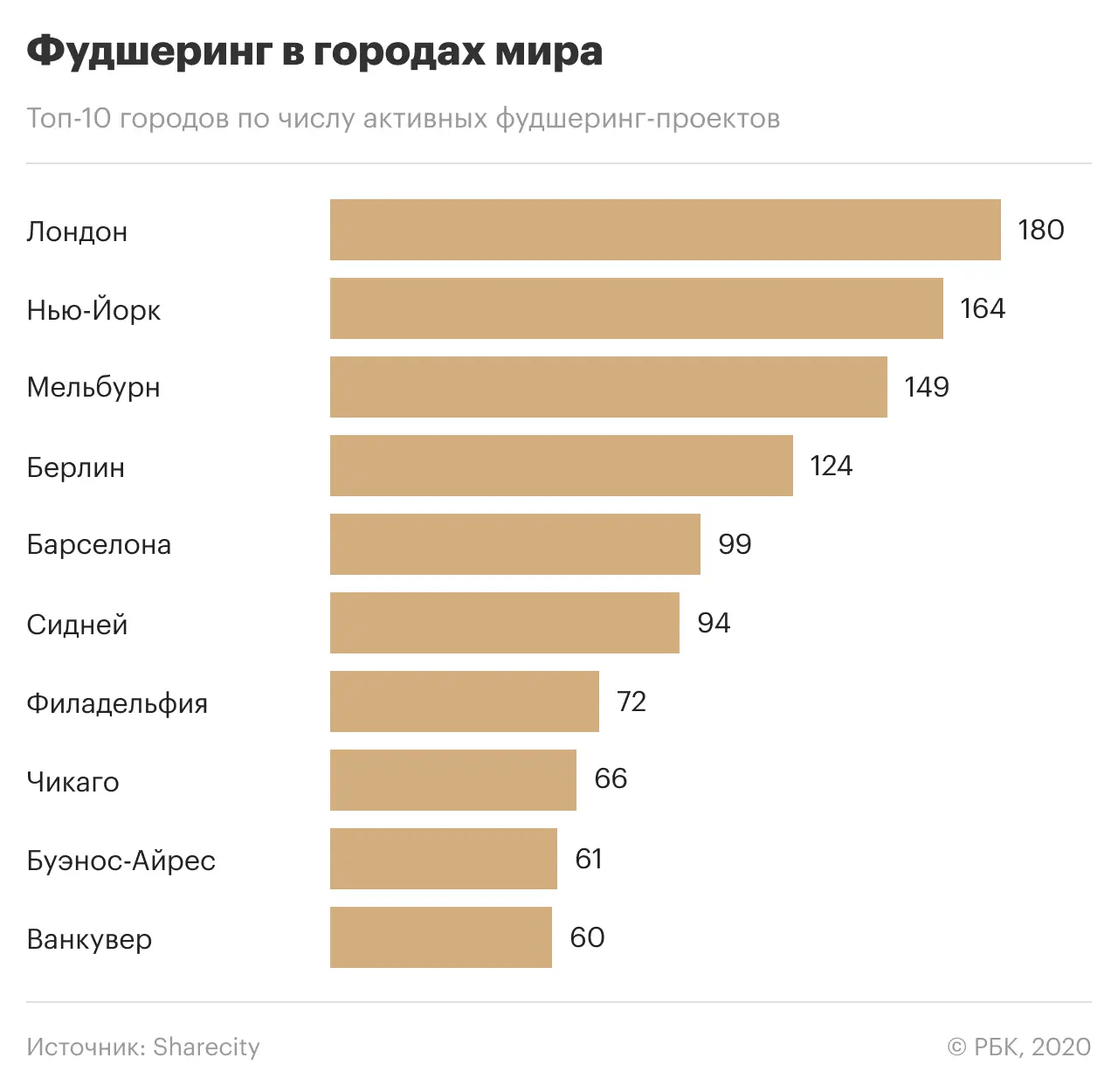

The Sharecity International Research Center is a platform for foodshare organizations where they can exchange experience and expertise. In addition, Sharecity data allows researchers to analyze the development of this phenomenon in different countries. The leader in the number of food-sharing projects among cities is London, there are about 200 such initiatives. Moscow is on the 88th place out of 100 cities represented in the rating.

The scaling potential of foodshare projects is huge. Only 5% of all projects work in more than one city, and only 1% – at the international level. Perhaps the next uber or airbnb will be delivering unsold vegetables, coordinating a chain of city gardens, or organizing field-cleaning trips.

There are many different forms of food sharing around the world. Unfortunately, most of them in our country do not have analogues.

Government regulation vs. trust institution

Foodsharing projects face misunderstanding from the state not only in our country. Many American initiatives are experiencing difficulties with the legalization and scaling of their activities. This is due to strong regulation in the field of food safety. In particular, the creators of the small farmers’ market Underground Market in San Francisco faced this problem, which in 2 years has grown from a small market in a private house to an event for 40 thousand people. Due to pressure from the authorities, which obliged sellers to provide certificates for their products, the initiative had to change its format – now they are conducting online courses.

Food security is an important aspect. But there is still an institution of trust. This controversy faced the founders of Josephine Cooks, a home-cooked service that was eventually forced to shut down because it recognized that it was impossible to fight corporate control of the food system. In the United States, there are laws regulating what food cooked at home can and cannot be sold (cottage food laws).

Small projects often face unfair competition from big playerswho do not want to give up their market share. For example, this often happens with seed swap projects. There are about 400 independent seed exchange communities in the United States, whose activities are very important, since the loss of genetic diversity is largely associated with the activities of corporations that monopolize the seed market.

It is even more difficult for projects that are engaged in the redistribution of products. Activists distributing food are being arrested around the world. The Food Not Bombs movement was founded in 1980 in California. By 1988, police had arrested more than a hundred members of the free food distribution movement because they could not provide a license to operate. According to the official position of Food Not Bombs, the distribution of food cannot be subject to government regulation.

European initiatives face similar problems. According to the 2017 European Union guidelines, food redistributed must be “certainly edible” and its source documented so that responsibility can be determined in the event of a health hazard. However, volunteer organizations often do not have enough resources to meet these requirements. The creators of Germany’s foodsharing.de system of public refrigerators were forced to defend their position: such refrigerators are a space for private exchange, and therefore cannot and should not be regulated by the state. In Germany, fortunately, no one was imprisoned for distributing food. But the fact remains that food security legislation prevents civil food-sharing initiatives from developing.

Is government regulation of food security effective and ensures optimal distribution of food among the population? Or can institutions of mutual responsibility and trust supplement and change existing norms? Perhaps one of these initiatives can solve the problem of throwing away food in good condition (in English there is a term food waste).

For food sharing projects, the social aspect of their activities and environmental responsibility are important. Most of them think about earnings last. Therefore, they need more support than businesses from the business environment.

Big Data and mapping

Any sharing projects are inextricably linked with technology. The popularity of social networks and landing pages is due to their relative simplicity, but as technology becomes available, applications are also becoming common. Here are some examples:

Wats Cooking (India) – sell homemade food

SEND (Tokyo, Japan) – sell farm products directly to consumers, bypassing retailers, shortening the supply chain and reducing potential waste

Wild Food (Houston, USA) – information sharing about edible plants

Byhøst (Copenhagen, Denmark) – dissemination of information about wild fruit plants in the city (urban foraging)

OLIO (UK) — peer-to-peer food sharing platform

The Ripe Near.me project is an example of using mapping (mapping) technology. He appeared in Melbourne, but later became international. The creators of the platform position it as a platform for the exchange and sale of products that are grown within the city. You can grow food in your apartment or garden and sell, give away or trade it. For the initiative, not only the process of production and sale of products is important, but also the activation of local communities through the exchange of food. Such a project could complement the city’s sustainable food systems policy.

One of the most successful projects in the field of redistribution of surplus food at the moment is FoodCloud. The initiative was launched in 2013 in Dublin and initially connected a Tesco supermarket, several small grocery stores and 6 charities. By 2018, the project was redistributing food from 4 partners to 7,5 charities across Ireland and the UK. FoodCloud has become an intermediary trusted by both retail chains and local charitable initiatives.

596 Acres is a food sharing project at the intersection of mapping and advocacy planning was founded in 2011 in New York. 596 Acres, like its successor 3000 Acres in Melbourne, began by looking for free municipal land to grow food together. 596 – this is exactly how many acres (240 hectares) of unused land the authors of the project were able to find in New York. These sites were mapped, then like-minded people gathered for the joint development of the territory. By 2018, about 40 public spaces had been created through this initiative. The creators of the project inspired many similar initiatives around the world, and also made their mapping service publicly available (Living Lots).

The concept of urban gardening, which can also be seen as an example of food sharing, is quite popular. Such projects include:

Himmelbeet – public garden in Berlin

Edible Garden City – over 200 public gardens in Singapore

Organization Earth is a public park area in the suburbs of Athens for educational projects in the field of sustainable development

Skip Garden and Kitchen – a farm and cafe in the center of London

Such green areas are useful for cities: social activity is growing, the psychological health of citizens is improving, food security and city autonomy are being strengthened, and the “heat island” effect is mitigated. However, often civil initiatives have an uncertain legal status, and municipal authorities have no precedents for working with such organizations.

There is another type of food sharing called gleaning. In the USA, for example, there are many organizations that, on a volunteer basis, help to develop “farm food sharing”: clayrs harvest crops for those farmers who, for various reasons, decided to leave food in the fields. Agnès Varda’s film The Gatherers and the Gatherer is dedicated to this phenomenon.

Foodsharing initiatives are diverse. The conditions and specifics of their activities largely depend on the context; universal models of development in this sector (so far) do not exist. Those who are going to launch similar projects should look at the experience of other countries and develop international contacts. Foodsharing initiatives largely support the trend towards a horizontal organization, because communication and the exchange of expertise is the key to success. Perhaps one of these projects will soon change the way we think about urban life and food systems.

More information and news about sharing trends in our Telegram channel. Subscribe.