Why shouldn’t you unconditionally trust your feelings? Polemic speech by psychologist Lisa Feldman Barrett.

Lisa Feldman Barrett, PhD in Psychology, Head of the Interdisciplinary Emotion Science Laboratory at Northeastern University (USA).

“Suppose you are listening to classical music on tape and you think the music is playing right in your head. It is obvious that this is not the case. Silly to ask: “Where is the brass region in the brain?” It’s much more reasonable to ask, “How does the brain create this experience—why does it feel like the orchestra is playing right in my head?” With this example, I want to start talking about emotions – or rather, about the false idea associated with them, which many people believe in. It seems to many of us that each emotion has a certain set of characteristics by which it can be recognized, and its own separate place in the body. It’s a delusion. Defining emotions in this way is like looking for clarinets and oboes in the brain.

Read more:

- How long do our emotions last?

Of course, we all know what it is like to experience anger, happiness, surprise and other emotions. At first glance, this division suggests that each emotion is fixed in the brain or another part of the body. Maybe a colleague who irritates you activates your “anger neurons” and this raises your blood pressure. You furrow your brows, scream, and feel the heat of rage inside. A parting with a loved one triggers your “sadness neurons” – you feel cramps in your stomach, despair seizes you, tears come to your eyes. Disturbing news turns on our “fear neurons” – the heartbeat accelerates, you freeze in place and feel how a wave of horror rolls over.

Such characteristics are considered to be unique biological imprints of each emotion. Research teams and high-tech companies around the world spend huge amounts of time and money trying to locate these fingerprints in the body. They hope to one day be able to identify emotions from facial expressions, body movements, and electrical brain signals.

Read more:

- What to do with violent emotions?

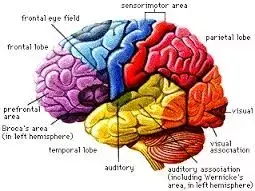

Some scientific studies, at first glance, support the idea that such prints exist, others refute it. Let’s start with neuroscience. Our lab analyzed an array of scientific studies from 1990 to 2011 relating to fear, sadness, anger, disgust, and happiness. On the computer, we divided the human brain into tiny cubes, like 3D pixels, and, based on the findings of the research, we tried to determine in which “cube” areas various emotions are activated. We discovered, that no part of the brain is devoted to any one emotion. We also found that all areas of the brain that are attributed to a particular emotion are also activated during non-emotional thoughts and representations.

Best known among the “areas of emotions” is the amygdala, which is located deep inside the temporal lobes. Since 2009, at least three dozen articles in popular media have stated that fear is related to neurons that “fire” in the amygdala. But only a quarter of the experiments we analyzed showed an increase in amygdala activity during moments of fear. It is known that many manifestations of fear, such as the flight response, do not involve the amygdala at all.

Another piece of evidence against the connection between the amygdala and the emotion of fear comes from a pair of twins known in the scientific literature as BG and AM. Both are born with a genetic disease that destroys the amygdala. BG almost does not experience fear – he feels it only in extreme situations, but AM in this sense is no different from ordinary people.

Of course, areas of the brain like the amygdala are important for emotions, but in general, there are no separate areas in the brain that are “tied” to certain emotions. For example, the amygdala is involved in many mental processes. Different areas of the brain are capable of producing the same emotion. We found that anger, fear, and other emotions are created by multipurpose brain regions that work in concert.

Perhaps there are clear signs by which emotions are manifested in our body – heartbeat, sweating, temperature, and so on? And again the answer is no. After reviewing more than 200 published studies involving nearly 22 participants, our lab found no consistent, single feature for any emotion. On the contrary, the body reacts in different ways each time, based on the situation. Even a rat, sensing danger (for example, the smell of a cat), will run away, freeze in place or fight, depending on the circumstances.

Read more:

- Qigong and emotional energy

The same with the human face. Many scientists take it for granted that our facial expressions accurately convey emotions (frown in anger, dilated pupils in fear, wrinkled nose in disgust). But a growing body of research says that’s not the case. When we apply electrodes to the face and accurately measure muscle movements, for example, in a moment of anger, we capture a variety of movements, and not just stereotypically furrowed eyebrows.

Charles Darwin became famous for disproving the idea of entities in biology. He noticed that a biological species is not a unique variety of living beings with once and for all given characteristics. Rather, a species is made up of very different individuals, each of which is better or worse adapted to its environment. Likewise with the words we use to describe emotions: “anger”, “happiness”, “fear” name a population of diverse biological states that vary depending on the circumstances. When you get angry with a colleague, in one case your heartbeat speeds up, in another it slows down, and in the third case it remains the same. You can frown or, on the contrary, smile, considering revenge. You can scream or remain silent. The variety of options in this case is the norm.

Read more:

- Chronic depression affects memories and emotions

This is important not only from the point of view of science, but also in a purely practical sense. When doctors ask the question “Is there a connection between anger and the occurrence of tumors?”, As if anger has a well-defined biological manifestation in the body, they are deeply mistaken. When airport security officers are trained to “calculate” deep emotions based on facial expressions and body movements, taxpayers’ money is wasted.

The ease with which we ourselves experience emotions and observe them in others does not mean that each emotion is clearly reflected in the face, or in the movements of the body, or in the brain. Instead of asking where emotions are located or what body movements can be used to detect them, it is much more interesting to ask another question: how does our brain create these incredible experiences?

See more at The New York Times.