Contents

Based on mRNA technology, the vaccine is designed to prevent Lyme disease, as well as other diseases that are passed on to humans by ticks. Animal studies are currently underway. What do we know about a breakthrough vaccine?

- Ticks are carriers of many diseases that are dangerous to humans

- One of them is Lyme disease

- Research indicates that we may soon receive a tick-borne vaccine

- More information can be found on the Onet homepage

The vaccine attacks the tick

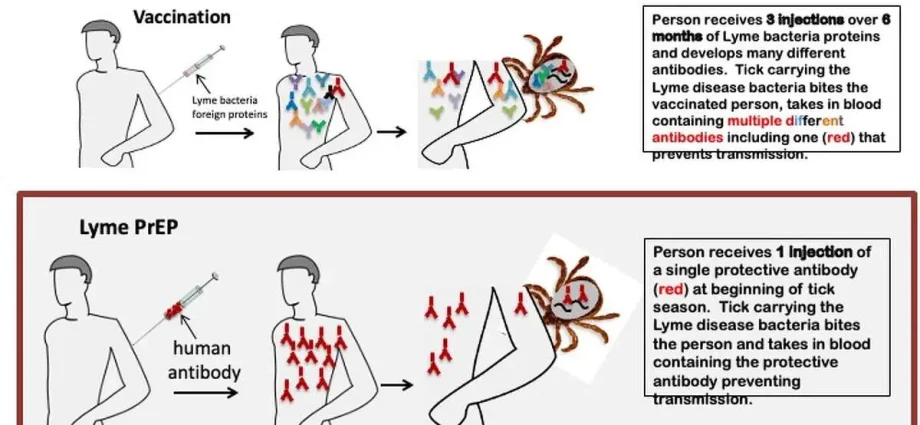

In the United States, Lyme disease is the most common infection that is transmitted from animals to humans. Every year, the deer tick (Ixodes scapularis) carries the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi there to up to half a million people. Lyme disease causes flu-like symptoms, the characteristic skin rash, and can also affect the brain, nerves, heart and joints, sometimes leading to permanent nerve damage and arthritis. Antibiotics may be effective in the early stages, but an increasing number of people – one estimate – at least 1,6 million in 2020 – are suffering from the chronic consequences of the infection. No human vaccine is currently available, although one is in clinical trials.

- Check also: They resemble moles. Few people know how dangerous tick nymphs are

Prof. Erol Fikrig of the Yale School of Medicine worked for 10 years on a novel vaccine that would target not the pathogen – but the tick that carries it. However, in June 2019, at a meeting in Killarney, Ireland, he heard immunologist Drew Weissman of the University of Pennsylvania describe a little-known technology at the time: a vaccine that uses messenger RNA (mRNA). Prof. Fikrig – as he recalls – immediately sensed the potential of the new technology.

Earlier vaccines were intended to target B. burgdorferi itself, but Fikrig believed that the bacteria could be stopped by a vaccine targeting the tick. Tick saliva contains factors that help spread the pathogen, but these proteins are “difficult to make in the laboratory,” says Fikrig, quoted on a science.org site. “The beauty of the mRNA vaccine is that … you don’t have to make the protein – the body does it for you.”

The rest of the text is below the video.

Preparation of mRNA for ticks

Thanks to the work of his team, a vaccine containing 19 separate mRNA fragments was created. Each encodes a protein or antigen from deer tick saliva (in comparison, mRNA vaccines against COVID-19 provide only one antigen).

“The mRNA vaccine must have saved us from COVID-19,” says Jorge Benach, a microbiologist at Stony Brook University who co-discovered Borrelia burgdorferi. – «Now [Fikrig] uses stunning technology … with more than one antigen at a time. (…) I think it will be very useful for future vaccines ».

“This is the first vaccine [intended for humans] against an infectious disease that does not target the pathogen” – pointed out prof. Fikrig.

- The editors recommend: New species of ticks from Africa. They are active almost all year round

What is happening with this vaccine?

So far, the mRNA vaccine given to guinea pigs turned the tick marks red and caused inflammation. Ticks ate poorly, fell off early, and often did not transmit the bacteria that caused Lyme disease. Scientists hope that one day the vaccine will work the same way in humans. Potentially the same mechanism of action may be used in many tick-borne diseases.

For many people, tick bites go unnoticed, allowing these arthropods to feed without interruption. The new vaccine, with multiple mRNA fragments that instruct host cells to make important proteins in tick saliva, prepared the guinea pig’s immune system to respond to tick bites. By 18 hours after the ticks were attached, most bites had turned into red, inflamed and (possibly) itchy wounds.

This is important because B. burgdorferi is rarely transferred from the tick to the host by 36 hours (the tick often remains attached for four days or more). When scientists removed the ticks shortly after inflammation developed at the site of the bite (as a bitten human could do), transmission of B. burgdorferi was blocked.

Much of the protection, however, will likely depend on whether people spot an itchy, red tick bite and manage to remove it early. When three infected ticks attached to guinea pigs and stayed on them until saturation, 60 percent vaccinated animals became infected (almost as many as in the control group). Whether vaccinated people will respond similarly to guinea pigs is not known yet. (PAP)

Author: Paweł Wernicki

Do you want to test your COVID-19 immunity after vaccination? Have you been infected and want to check your antibody levels? See the COVID-19 immunity test package, which you will perform at Diagnostics network points.

Also read:

- Did you catch the tick? Absolutely don’t do these things!

- What are the tests for Lyme disease?

- The “missing element” of Lyme disease was discovered. When is the vaccine?

The content of the medTvoiLokony website is intended to improve, not replace, the contact between the Website User and their doctor. The website is intended for informational and educational purposes only. Before following the specialist knowledge, in particular medical advice, contained on our Website, you must consult a doctor. The Administrator does not bear any consequences resulting from the use of information contained on the Website. Do you need a medical consultation or an e-prescription? Go to halodoctor.pl, where you will get online help – quickly, safely and without leaving your home.