Contents

In Soviet times, medical sobering-up stations became not only a way to combat drunkenness and alcoholism of the population, but also an element of folklore. Next, we will figure out what is the history of the emergence of such institutions and why they ceased to exist, and also whether they can appear again.

What is a sobering-up

Sobering-up stations were medical organizations where citizens were brought in varying degrees of intoxication and kept until they were completely sobered up. So the state solved two problems: it fought against the drunkenness of the population and reduced the number of crimes committed under the influence of alcohol. According to the legislation, the appearance of persons in an inadequate condition in public places was regarded as a violation of law and order.

Until 2011, citizens were taken to sobering-up stations, where, if necessary, drunken people were provided with medical assistance. Subsequently, the government decided to liquidate the institutions and transfer the functions of sobering up to health organizations. As a result, drunkards began to be delivered to the territorial bodies of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which led to a sharp increase in mortality due to untimely provision of medical care.

Currently, the topic of returning the sobering-up stations system is periodically raised, but so far the state has not taken practical steps in this direction.

History of sobering-up stations in Russia

The first mentions of institutions for the violent sobering up of citizens are found in documents of the XNUMXth century. The boyar Fyodor Rtishchev, known for his activities in the construction of civilian hospitals and almshouses, ordered his assistants to travel around Moscow daily, pick up drunks lying on the streets and deliver them to a specially organized shelter.

November 7, 1902 is considered to be the official date for the appearance of sobering-up stations in Russia, it was then that a special institution for the detention of drunkards was opened in Tula. The shelter appeared on the initiative of the doctor Fyodor Arkhangelsky, who was supported by the city council. The doctor was driven by the desire to save the drunken Tula masters from death in severe frosts, since many of them were skilled gunsmiths. The shelter was maintained at the expense of the city budget.

Arkhangelsky was well aware that alcoholism in Russia leads not only to high mortality, but also to the degeneration of the nation, so he ordered the creation of several departments in the institution at once, including a medical outpatient clinic and a shelter for children of drinking parents.

Drunks were delivered by a coachman, and if necessary, they received paramedical assistance. Soon, shelters of this kind were opened in all major Russian cities, and Fyodor Arkhangelsky received an honorary silver medal for his initiative.

After the revolution, all institutions ceased to exist. The first Soviet sobering-up station opened in Leningrad only in 1931. Nine years later, on the orders of Lavrenty Beria, all organizations of this kind came under the jurisdiction of the People’s Commissariat of Internal Affairs and remained under the control of law enforcement agencies until the very closure.

Who was taken to the sobering-up station

The regulation on sobering-up stations established the procedure for the operation of institutions and determined the categories of citizens who could be taken there. The order of the Ministry of Internal Affairs detained persons in a state of moderate and severe alcoholic intoxication, who, by their appearance, insulted public morality and violated order. The exception was military personnel, people’s deputies, war heroes, pregnant women and the disabled – they were assisted in medical institutions.

They tried to find out the identity of the drunks immediately, they took money and documents. After being examined by a paramedic, the most severe measures could be taken to sober up. To bring a person to his senses, he was placed under a cold shower, and if he resisted, he was tied to a bunk. There were also abuses: a drunk in a sobering-up station could be shaved bald, and sometimes even beaten. During the period of the anti-alcohol campaign, employees of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, in an effort to fulfill the plan, could pick up even slightly tipsy citizens.

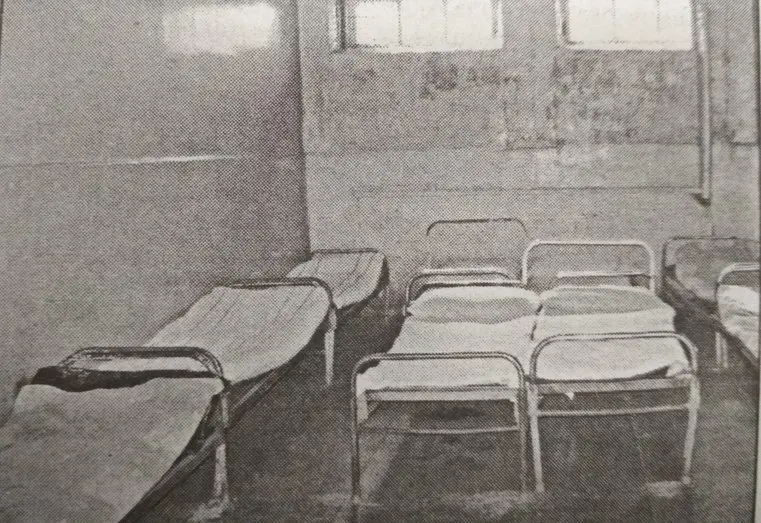

The sobering-up stations were equipped with bunks for sleeping or metal beds with a pillow and a blanket. After sobering up, the citizen was obliged to pay a fine of 15 rubles, which at that time was a rather large sum.

The offense was reported to work. For a regularly drinking worker, this fact did not spoil the reputation, but for mental workers, the paper from the sobering-up station threatened with troubles and problems with their future careers.

The end of the era of sobering-up stations

Russian sobering-up stations ceased to exist in connection with the updated legislation on the protection of the health of citizens. On its basis, any medical assistance should be provided to Russians only on the basis of their voluntary and informed consent. The last twelve sobering-up stations were closed in 2011, some of them were converted into medical facilities.

Foreign experience

The former countries of the socialist camp adopted the Soviet experience of working with drunken citizens. For example, in Poland one night stay in such an institution costs 300 zł.

The laws of most American states prohibit the detention of drunks, if they do not violate public order and behave adequately. Most European states have a similar policy, and in Canada and Sweden, the police simply deliver alcohol abusers home, while charging a small fee.