Adapting to consumer demands for minimalism, companies are moving towards simplification of brand designs and even a complete rejection of logos. Understanding how design evolves through debranding

The growing distrust of brands and the messages they convey, as well as the trend towards individualization, are pushing companies towards debranding. Its manifestation can vary: it can be a simple removal of the brand name from the logo, no mention of it in advertising, or a simplification of its visual presentation.

Less – more

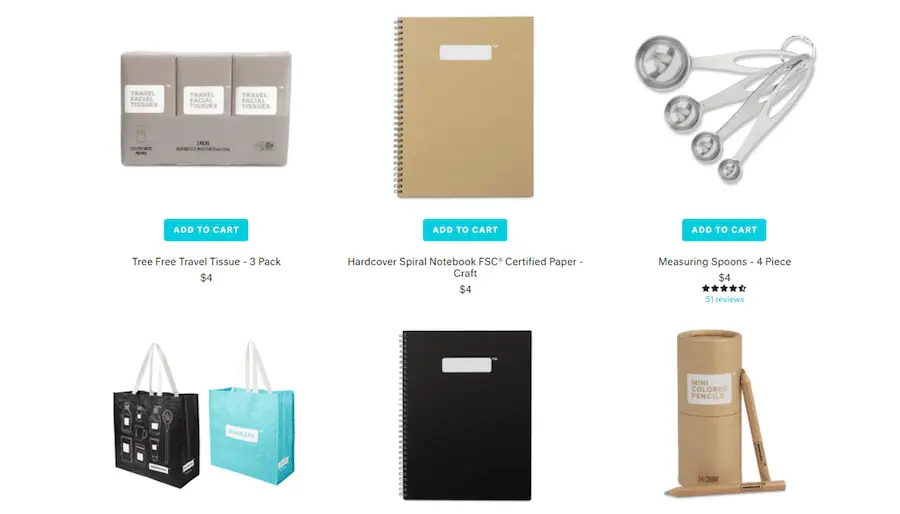

One of the pioneers in this trend can be considered the Japanese company MUJI. It produces household items ranging from kitchen utensils and furniture to stationery and casual wear. A distinctive feature of MUJI products is the absence of obvious branding – even the branded sticker can be easily torn off. All elements of the company’s brand embody the principle of “Less is more”.

MUJI focuses on the product itself, which also helps to reduce waste. In addition, simplicity and versatility allow customers to easily personalize purchased items. For example, they can choose to write on the cover of a notebook or embroider on a cloth bag at the MUJI service, and this option is usually free.

The company replaced traditional brand advertising with publications about the philosophy of its products, specialized events and lectures in stores.

MUJI is not the only, but perhaps the most notable example of a company that has gone down the path of debranding. Among others, we can single out the Brandless fixed price marketplace, where not a single product reflects the relationship to a specific brand-manufacturer.

Logo Simplification

In the early 2010s, the debranding trend began to be adopted by larger and more well-known companies. They could not completely abandon branding and opted for an alternative in the form of simplifying their logos.

The first notable example was Yves Saint Laurent, which, as part of a rebrand in 2012, switched from its signature style to a simple, bold Grotesque font. Within a decade, brands such as Diane Von Furstenberg, Calvin Klein, Burberry and Balmain came to use a simple type in their identities.

In parallel, the identity began to change for brands that produce cars, representatives of the entertainment industry and consumer goods – the logos of Pringles, Pepsi, Lay’s, Durex, Intel, Toyota, Burger King, Warner Bros, Dunkin’ Donuts have lost detail and depth.

One of the reasons for this was also the need for versatility in the image of logos both on paper and in digital form: the Internet limited their sizes. If earlier the smallest “canvas” for brand creative was the size of a business card, now the logo should even fit on the favicon (website icon in the browser).

For example, the trend towards simplification can also be attributed to the line of basic products for retail chains: for example, “Red Price” for “Pyaterochka” and “D” for Dixy.

When debranding is useful and when it is not

A company may decide to debrand for various reasons: for example, if it decides to attract customers by personalizing products. This is what Coca-Cola did when it started producing bottles with names.

Also, the company may try to get rid of any element in the branding that has acquired a negative connotation over time. For example, in 1991, the fast food chain Kentucky Fried Chicken was renamed KFC: at that time, the ideas of healthy eating and the harm of fried food were becoming more and more popular in the United States, so the word fried in the name could alienate visitors.

Another manifestation of debranding is to “modestly remain silent” about the parent company of the brand in order to “hide” the connection between the “independent” brand and a large corporation. For example, payment service Venmo is owned by fintech giant PayPal, while craft beer makers Bluepoint, Lagunitas, and Ballast Point are actually owned by Anheuser Busch, Heineken, and Constellation Brands, respectively.

There have been cases when debranding has done companies more harm than good. For example, when Sony Pictures decided to sell one of their movies on DVD without a trademark, many consumers thought the product was fake and tried to return it.