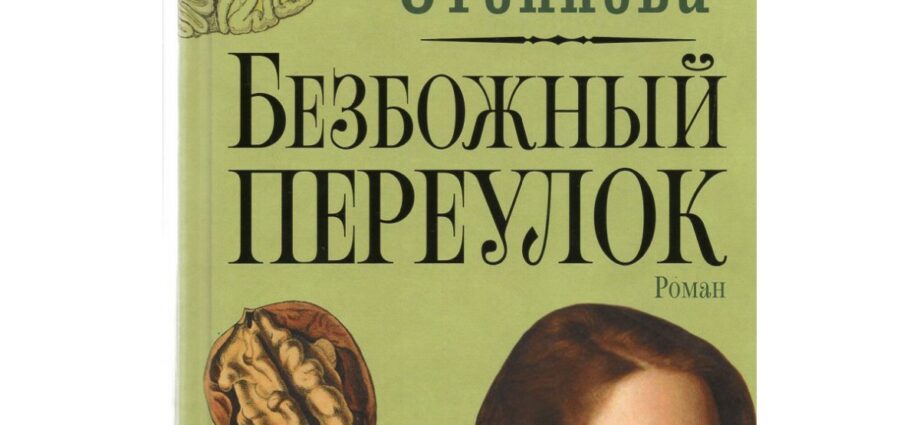

The third novel by Marina Stepnova will delight fans of The Women of Lazarus with a recognizable author’s style – details of everyday life, honey-colored metaphors, family history. But the hero is different. He does not claim the exclusivity of Lazar Lindt, a brilliant physicist, on the contrary.

“Godless Lane” is a novel about the notorious, given from birth, everyday life, the middle way and deep Russian “longing for Tuscany.” Ivan Sergeevich Ogarev, a Soviet doctor, as befits an intellectual, lives in books and art albums, moving from one to another, trying on characters and comparing the techniques of great painters just like that, for the soul. A sad childhood of the late 70s with a tired mother and a tough father, senseless sitting at school, a random choice of the profession of a doctor, an army, a wife, a job – a long attempt to fit into the system, grow together with the country. A series of mistakes and disappointments. A triumphant career awaits him. All that remains for him is to turn into any of Chekhov’s doctors, if not for the generous author. Malya appears – golden, changeable, ready to cry and laugh every second, elusive, impossible in his life, with a single request: please, let’s go to Italy.

This is the main question of the novel: does such happiness exist? Is it possible to jump from the cold, dull Moscow outskirts into the narrow streets of Italy, to generous beautiful women, a blooming world and a warm wind? Is it possible to get out of art albums and look firsthand at the chiaroscuro of the great masters and the blessed Italian land in the rays of the setting sun? And what is with him, with Ogarev, such that he finds it hard to believe? Why is Malya in Italy like a fish in water, but he is so uneasy? Italy – laughter, wine, cheese – is Russian “one hundred percent like alcohol” able to be reborn for her? Malya was born in 1987, when, it seems, the whole country was already in pain with Chaadaev’s longing for world culture and asked to go to Italy. And even went. And now there is still no unequivocal answer, whether it was good or bad, and Stepnova, of course, does not have one either. But the fact that she manages to reformulate eternal questions for Russia in the context of today is the undoubted value of the novel.

AST, 384 p.