Contents

How the brain makes us spend money, how knowledge about its work will help us not to go broke, and where does the pain come from?

What the marshmallow test says about our economic decisions

Imagine: you are sitting at the table, in front of you is a marshmallow and nothing but it. The person who invited you to this table says that he will leave for 15 minutes, and when he returns, he will bring you a second marshmallow. But on one condition – if during this time the first remains untouched. But then you can eat both. A 15% increase in XNUMX minutes looks like a very good deal. But only if you are an adult. For children, such a delicacy in thirty centimeters is a real temptation.

The Marshmallow Test is one of the most famous experiments in social psychology. It was conducted in 1972 at Stanford University by psychologist Walter Mischel. He studied children’s ability to delay gratification and resist momentary desires. But the most interesting thing turned out many years later. In 1990, Michel found that those who waited for the second marshmallow as young adults were noticeably more successful in school and in general in life. Since then, the ability to resist impulsive desires has been considered one of the main factors in life success.

The Marshmallow Test for Adults is Their Financial Decisions. Buy this beautiful shirt now or save it for a vacation. Dine in an expensive restaurant or buy home groceries for the week. Take a car on credit at a high percentage or continue to travel by metro.

Traditionally in economics a person is perceived as a rational subject: “I think, therefore I spend money.” However, more and more often questions arose about its rationality.. As an answer to them, neuroeconomics arose – it studies how the contents of our head influence our decisions.

Pain, control and reward

We feel good when we receive money, but we feel bad when we spend. Which is not surprising, because the larger the amount with which we part, the more active the pain center in our brain – insular portion. It is also active when we smell an unpleasant smell or expect that we are about to be hit painfully.

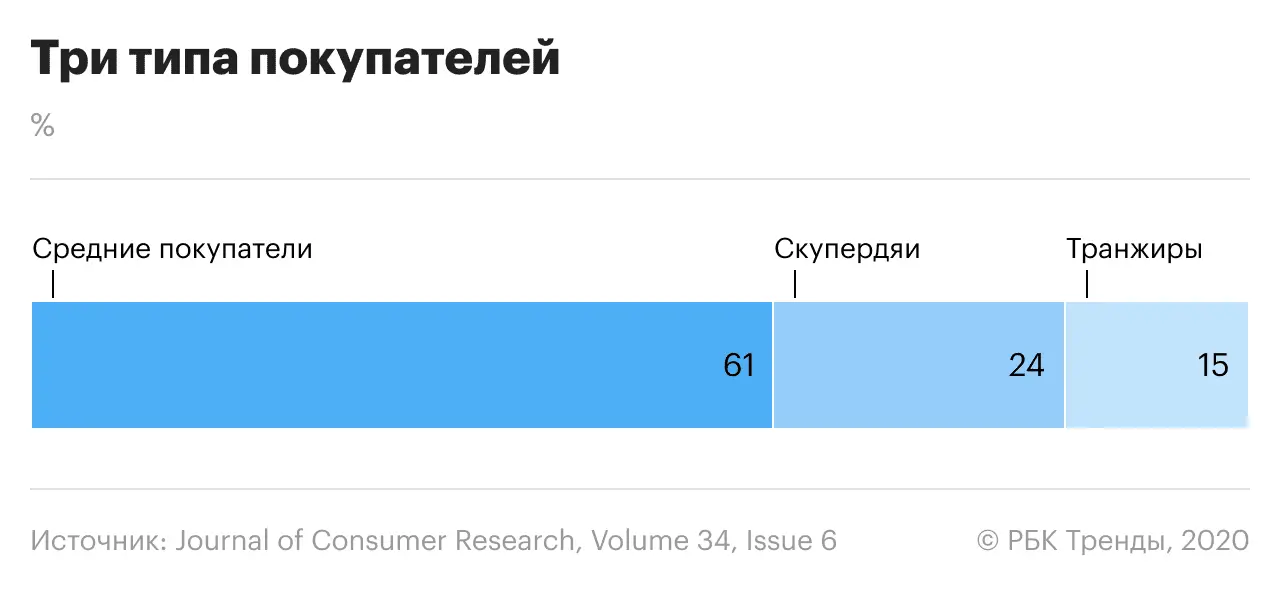

The financial “pain threshold” can be different. Neuroeconomists even made a special scale. At one end are “spenders” who are willing to spend a lot until they reach the threshold. On the other – “mean” who find it difficult to fork out even for the bare necessities. According to the researchers, this does not mean that some are more rational than others – they are all driven by momentary emotions.

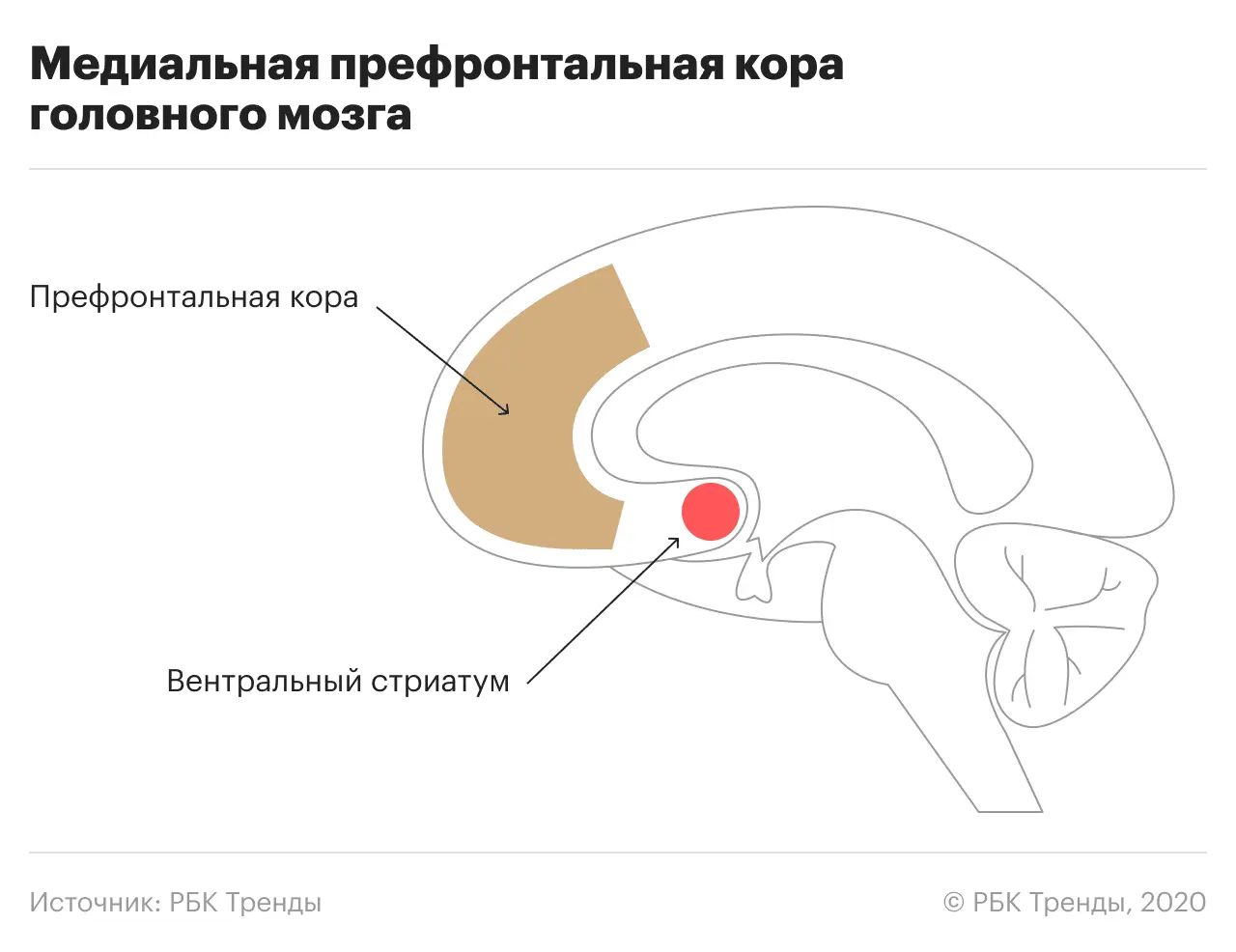

In addition to the pain center in the brain, there is also a reward center – the ventral striatum. He reinforces this with dopamine and makes the “Wishlist” characteristic of a person – food, sex or a new gadget – so desirable. When, 40 years after the “marshmallow test”, its participants were placed in an fMRI scanner, those who did not wait for the second marshmallow were more active in the “reward center”.

In those who waited for the second marshmallow, the brain also worked in its own way – the prefrontal cortex was more active. This is the area of the brain that, in principle, makes us human – here is both rational thinking and global plans for life, for the sake of which one has to postpone momentary pleasures.

Normally, the prefrontal cortex balances impulses from older pain and reward centers.. You liked the thing – dopamine was released, the “I want” reaction went. Then you saw the price and felt a surge of negative emotions. As a result, this zone makes a decision: is it worth it or not.

When the balance between emotions and intellect is disturbed, there is a tendency to impulsive behavior, including financial behavior – to go and spend half the salary on the shoes you like.

How to deal with impulsive spending

1. Avoid temptation

To think that this time you will definitely overcome the temptation is very reckless. Especially if you yourself know that you tend to indulge weaknesses. As science journalist Irina Yakutenko explains in Will and Self-Control, there is no “willpower”—only the ability to resist impulsive behavior.

This ability largely depends on physiology and even genetics. In a weak-willed person, the synthesis of the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin may be impaired. And the reason for this is a slight difference in the variant of the gene encoding the protein that is involved in their synthesis.

If you know that you sin with impulsive purchases, then never carry large sums with you. And when the salary comes, withdraw money from the card and put it on a deposit or in a hard-to-reach place.

2. Don’t buy right away, take a break

Did you like something? Do not buy it right away, try to wait – 15 minutes, an hour or several days, depending on the amount of the purchase. At least because the frontal lobes – where the prefrontal cortex is located – may not have time to slow down our emotional impulses. They just need time to calculate the possible outcome of their actions.

3. You can “please yourself” with sports, and not just shopping

After a busy day or week at work, sometimes you want to go and “please yourself”. This “please” suggests that we have some limited resource of willpower that needs to be compensated. In fact, the brain simply does not have enough dopamine, serotonin or endorphins and it is looking for ways to stimulate their release, preferably simpler. Yoga or sports will provide an influx of “pleasure hormones” no worse than shopping.

4. Do not go to the store hungry

This is not just about the store. In general, do not make financial and any other responsible decisions on an empty stomach. In this state, it is more difficult to control emotional impulses. The brain needs glucose to function. When it is not enough, he copes with tasks worse, and evolutionary new zones are the first to “turn off” – just those that are responsible for self-control.

5. Don’t spend money in a bad mood

It is worth monitoring your emotional state – anxiety or stress can affect the metabolism of neurotransmitters and prevent the prefrontal cortex from performing its “control functions” normally. It is better to wait out a bad mood – happy people spend less money.

6. Recognize manipulation

The magic of media and advertising is stronger than self-control. People used to watch commercials on TV, now they watch YouTube unboxing videos. Commerce has moved online and uses the most sophisticated advertising tools. You are offered products that best suit your preferences. Application interfaces are designed to suck your attention and resell to the advertiser. It is impossible to resist this. But if you know how it works, you can avoid unnecessary expenses.

7. Spending Less Challenge

Try to turn the economy into a quest, into a game. For example, go grocery shopping for a week and meet a clearly set amount. Start a challenge with your friends – who will spend less. The very mechanics of the game, where not spending money is the desired action, can link savings to the pleasure center. You can also keep a list of what you refused to spend money on – this can once again amuse your pride and add “pleasure hormones”. There are also more global options – for example, No Spend Year, when you do not buy anything for a whole year, except for the bare necessities.

marshmallows for the poor

In May 2018, an article was published with the results of a new “marshmallow test”. Psychologists Tyler Watts, Greg Duncan, and Khaonan Kuan repeated Michel’s experiment, but on a more diverse sample. There were more than 900 children instead of less than 90 for Michel. The mothers of more than half of them did not have a college education at the time of their birth (Mishel had mostly children of Stanford employees). With children, they first conducted a “marshmallow test” at 4 years old, and then studied their academic performance and behavior at 15 years old.

The results were very different. The ability to delay gratification still predicted future success, but twice as bad as previously thought. The study showed: the ability to wait for the second marshmallow is an important success factor if you are from a good, wealthy family. Children from poor families take the first marshmallow because they know that no matter what anyone says, the second may simply not be.

Our ability to resist impulsive desires is determined not only by genes or brain function, but also by the environment. Our desire to spend money can talk about how not only we ourselves are arranged, but also life around us – in which there is less and less confidence in the future.