Contents

The human heart was thoroughly examined very late. For many centuries, it was believed that the main blood vessels originated in the liver. The most powerful minds in the history of world science have worked to discover new secrets of the heart. Below we publish excerpts from the book “New Map of Miracles” by Caspar Henderson, which was published by Marginesy.

- The Roman physician Galen, who lived in the XNUMXnd century AD, considered the liver, not the heart, to be the center of human life. This belief prevailed for many years

- At the beginning of the XNUMXth century, Leonardo da Vinci examined the human heart in detail. discovered the role of valves. The research results remained forgotten for nearly five hundred years

- William Harvey, in turn, in 1628, stated that blood must flow in a closed circuit

- More information can be found on the Onet homepage

The human heart – when does it begin to beat?

First we begin to hear – five months after conception, when the human fetus is about half the size at birth, the eardrums and the inner bones of the ear are almost the same size as an adult. The auditory nerves are sufficiently developed to conduct signals, and the temporal lobes of the brain, which are responsible for processing sounds, are already working. The fetus hears low-frequency sounds, one of the first is the rushing of blood pulsating through the mother’s aorta with every beat of her heart. A six- or seven-month-old organism can hear practically the full range of its mother’s voice, although it reaches it in a slightly muffled form. Certain tones and patterns of sounds, spoken or sung, can induce him to start or stop moving, it also happens that the mother and the child learn to “talk” to each other – the fetus reacts to some sounds, especially melodic ones, and the mother, by sensing this, consciously repeats them.

Thanks to ultrasound scans, the first sound a baby makes that parents can hear today is the beating of the tiny heart inside the mother’s womb. When I heard them for the first time as a future father, the pace of this rhythm – well over a hundred beats per minute – struck me as exciting and terrifying at the same time. Seeing my indistinct expression, the nurse softly explained that this frequency was perfectly normal for a child at this stage of development. It calmed me down a bit, but I was still sitting speechless.

When viewed in the context of the entire animal kingdom, the heart of a human child beats neither very slowly nor especially fast. A hummingbird’s heart beats over a thousand beats per minute. In a clam this happens twice a minute when it is resting, and in moments of excitement the pulse increases to twenty beats per minute. Nevertheless, the rapid heartbeat of a fetus, newborn or toddler – the rhythm of life just beginning – remains for me one of the most delightful phenomena in the world: beautiful and at the same time disturbing in its tenacity.

In stress, joy or excitement, we quite often become aware of – or we think so – our own heartbeat. We do not perceive any of our organs in this way, and the twist of the intestines or an upset stomach are a completely different pair of wellies. This experience only strengthens our sense that the heart plays a key role in the matters most important to our existence. This approach is, of course, nothing new. In ancient Egypt, the heart, that is Ib, was considered the most important manifestation of the soul, and happiness was referred to as Awtib, which literally means “the breadth of the heart”. All organs were removed from the mummified corpse, leaving only the heart, so that the god Anubis could compare its weight with the pen of Maat, the goddess of truth, harmony and justice, and assess whether a man lived his life well.

To this day, in various traditions, they are perceived as the essence of what is most valuable in us. In a Hindu devotional song chanted during meditation LaghunyasaAccording to which Shiva – the Supreme Being who creates, protects and transforms the universe – lives in the heart. During Sufi prayer, dancing dervishes rotate from right to left around the axis of the heart to express the love they embrace with all mankind. On the other hand, from the achievements of the European Romantic tradition, many would agree with John Keats’ declaration: “I am sure of nothing but the sanctity of the gusts of heart and the truth of the imagination”. According to recent scientific studies, people who are aware of their own heartbeat are also better able to read the emotions of others.

Attempts to maintain a sense of decency in dark times often appealed to similar associations. In the XNUMXs, fearing that the great distances and abstract language would obscure the real scale of the nuclear attack by the American president, lawyer Roger Fisher suggested that a young officer constantly accompanying the head of state should not carry the codes for the warheads in a suitcase, but had them hidden in a small capsule surgically sewn underneath. heart. Then, if the president had decided that the murder of tens of millions of people was really necessary, he would have to pick up a butcher’s knife and personally cut the man’s heart to get the combination. Fisher said that when he introduced the idea to his friends from the Pentagon high command, he heard:

“God, it’s terrible … [The President] might never push a button.” But the heart can also be tricked into the service of systems of control and oppression. In Dave Eggers’ satirical novel “The Circle” from 2013, the main character of Mae Holland wears a pretty pendant with a miniature camera built right in the middle of her heart, as part of a new, universal surveillance system. In the real world, some companies are already starting to introduce sociometric sensors that, when hung around the neck of employees, monitor their every movement and interaction with the environment.

Discovery of the heart

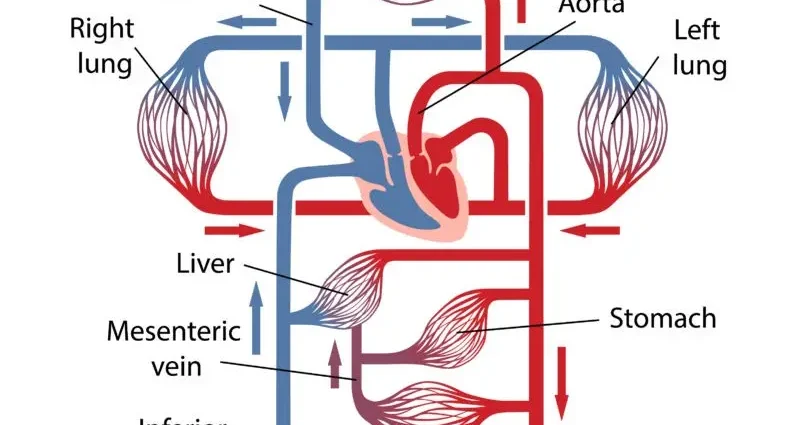

Throughout most of human history, we have known very little about what the heart actually is and how it works. It may seem strange to us, people brought up in modern industrial societies, but the notion that the main function of the heart is to pump blood to all parts of the body is by no means intuitive. The circulation of blood around the body is no more noticeable to the naked eye than the fact that the Earth orbits the sun. The veins and arteries seem to disappear somewhere deep in the tissues, and the capillaries that we know today connect them, closing the circuit, are so tiny that they can only be seen under a microscope.

The Roman physician Galen, who lived in the XNUMXnd century AD and his concepts dominated European medicine for over XNUMX years, was impressed by the size of the liver and its central location in the human body. It was this organ that he considered to be the main center of life. He taught that blood is one of the four humors, or body fluids (the others are bile, black bile, and phlegm). According to him, the food digested in the belly was sent through the portal vein to the liver, which transformed it into blood and filled it with what Galen called it “natural spirit”. From there, this cocktail traveled heavily through the main veins to all the tissues of the body that consumed the spirit, and then the blood returned the same way for another dose. At the same time, some of the blood was to be directed to the right side of the heart, where it was in contact with the air that came from the lungs. As a result of this collision, a kind of fire was created and hence the heat, so characteristic of a living body, was obtained. The heat, however, did not burn the blood, but it was cleansing, and it, having penetrated somehow through the septum in the center of the heart into its left ventricle, produced a “life-giving spirit”, which then flowed through the arteries to increase the speed of movements in the body and thoughts in the brain.

Galen’s theories about the heart were completely untrue and were long ago rejected by medicine. But his doctrine of the four humors – in a modified form of the four temperaments – proved surprisingly vital. It hides behind concepts such as the Myers-Briggs Test for different personality types, which was used quite extensively at the end of the 1993th century. It even survived in the minds of scientists from an imaginary future. In the XNUMX science fiction novel “Red Mars” by Kim Stanley Robinson, describing the colonization of this planet in the XNUMXst century, psychologist Michel Deval is surprised to discover that this ancient classification is useful for analyzing the personality types of the first colonists. Perhaps the enduring charm of Galen’s theory is that it seems to reveal to us the secret of the corporeal being, leaving no room for doubt or understatement – and this is especially welcome in the face of sickness or anxiety. Meanwhile, modern medicine, the one at the highest level, accepts complexity and uncertainty. The human body, Dr. Atul Gawande explains, can be “frighteningly convoluted, unfathomable, difficult to decipher”, and this awareness can be less comforting to us than false hope.

Da Vinci’s discoveries about the heart have waited five hundred years

Leonardo da Vinci made one of the greatest steps towards learning the nature of the heart at the beginning of the XNUMXth century. In some respects, his in-depth analysis remained unexplored until the late XNUMXth century. In the period roughly from 1508 to 1513, a few years before his death, Leonardo began a detailed study of human anatomy – the skeleton, muscles, tendons and nerves, the reproductive system and the most important organs, especially the heart.. Being a military engineer as well as a talented artist, he used his knowledge of levers and fluid flow and the subtle movements of living beings in his research.

He produced anatomical sketches of an unparalleled degree of precision, not to mention admirable lines. Perhaps after several decades of trying to capture in his paintings the admiration for the external form of man, Leonardo finally went in search of beauty which, using the words of the writer Ursula Le Guin, reaches not only the depth of the skin, but the depth of life.

Working most of the time on beef and pig hearts, and only later on human hearts, Leonardo realized that this organ was above all a muscle. He found four cavities where, according to Galen, there were only two, and he discovered that the upper pair, or atria, contracted simultaneously, followed by contraction of the lower cavities, or ventricles. The wrist pulse turned out to be in sync with the heartbeat, and our hero attempted to calculate the cardiac output (the amount of blood that the heart moves per minute). He found the valves were unidirectional, which was incompatible with Galen’s theory of the uninterrupted flow and outflow of blood. He also concluded that turbulent flow aids in the opening and closing of valves – a phenomenon that was not fully understood until the end of the XNUMXth century.

He discovered and sketched the bronchial arteries, and described the septic-marginal trabecula. He rightly considered it to be a muscular bridge between the walls of the right ventricle, which prevents its excessive distension. Da Vinci’s numerous observations were so insightful that it is hard to believe that he might not have guessed that the heart pumps blood to all parts of the body. In his notes that have survived to this day, however, there is no unequivocal statement of this conclusion. Leonardo never published his research on the heart – the above discoveries were completely unknown in his time and were forgotten for nearly five hundred years until these sketches and notes finally fell into the hands of experts. As a result, Leonardo’s successors had to act in the dark, deprived of access to the knowledge he had acquired about the heart.

In “The Structure of the Human Body”, published in 1543, Andreas Vesalius presented his maps of the inner world made using the standards of the fine arts as well as a rapidly developing cartography based on empirical observations. Vesalius, who taught anatomy at the University of Padua, performed extremely meticulous autopsies and was therefore able to correct many of Galen’s errors, such as the notion that major blood vessels originated in the liver. He also challenged the theory that blood was seeping through invisible pores in the septum of the heart. But he was unable to completely throw off the burden of tradition and held up the Galenic view that different types of blood flow through our veins and arteries. Nevertheless, Vesalius’ skepticism and his belief in direct observation inspired others to continue to question Galen’s authority.

Galen’s theories refuted after several centuries

The final break with Galen’s teachings was due to William Harvey, who studied medicine in Padua in the early XNUMXth century under the tutelage of the immediate successors of Vesalius. Harvey carried out daring but gruesome experiments. He cut the dogs’ arteries to measure how much blood gushed out of their still beating hearts. It became clear that the liver would not be physically able to produce as much blood as the heart pumps in minutes, let alone an hour. From a daily perspective, we are talking about tons of blood. The only explanation, stated by Harvey in 1628, is that blood must flow in a completely closed circuit.

In recognition of this discovery, Harvey was hailed as the Galileo of Medicine. But his theory was still vague in some respects, still alluding to some aspects of Galen’s vision, and retaining elements of mysticism. For example, ignorant of the existence and nature of oxygen, Harvey wrote that blood is “volatile” and “filled with spirit” which heats up and cools according to Galenic laws. He also supported the idea – advocated by his friend Robert Fludd, a physician and representative of the Hermetic philosophy – that circular motion is an expression of God’s will. In his work “Utriusque cosmi”, a monumental history of the macro- and microcosm published between 1617 and 1621, Fludd wrote that when God created the world with his divine breath, it moved in a circle, which was also reflected in the circular movement of the sun in the heavens. And as in heaven, also on Earth, the sun, through the circulating air currents, sent the divine wind to our planet, where – in the form of the “quintessence of air” – it penetrated the human body through the lungs, and then went to the heart, which led him into the next, much less circulation.

Descartes was one of the first and most influential defenders of Harvey’s concept of blood circulation in the body. He emphasized the mechanical aspects of this theory, comparing the heart to a pump and a clock. Today this may seem an oversimplification to us, but both analogies contain a good deal of truth. The reliable regularity of the work of a healthy heart led Galileo himself to one of his most brilliant ideas. Apparently, several decades before Harvey discovered blood circulation, young Galileo observed candelabra dangling under a church vault and, measuring time with his own pulse, found that the period of their fluctuations was the same regardless of the degree of swing.. This prompted him to base the clock mechanism on the pendulum, and in 1637 – at the end of his life, when he was under house arrest for preaching that the earth revolves around the sun – he sketched a design for such a device. Although he did not have time to construct it, Christiaan Huygens did it in 1656, fourteen years after his death. The accuracy of the invention far exceeded the accuracy of clocks, it reduced the margin of error from about fifteen minutes to fifteen seconds a day.

For Descartes, the body was a machine, a material object that received instructions from the immaterial mind and soul through the pineal gland – a structure located in the center of the brain and acting a bit like the XNUMXth-century equivalent of a Wi-Fi receiver. Today, this model is not accepted even by those who clearly distinguish the shell and the soul, but this does not mean that the body and its internal organs, including the heart, have nothing to do with the mechanisms. In fact, they are mechanisms far more sophisticated and complex than Descartes could have imagined, and, apart from everything else we know about their nature, by looking at them from this perspective, we can surely broaden our understanding of miracles.

We encourage you to listen to the latest episode of the RESET podcast. This time we devote it to one of the ways to deal with stress – the TRE method. What is it about? How does it release us from stress and trauma? Who is it intended for and who should definitely not use it? About this in the latest episode of our podcast.