It is difficult to imagine our world without epidemics. Religious schisms, the destruction of serfdom, colonial conquests – in one way or another, terrible diseases affected everything. And there are no less positive consequences than negative ones.

The COVID-19 coronavirus epidemic that has swept the whole world has demanded a lot of effort from many people to fight it. Doctors are treating the infected every day, scientists are hastily developing tests and continuing to search for a vaccine, officials and entrepreneurs are puzzling over the choice of strategies to simultaneously ensure the isolation of a large number of people and maintain economic ties in society.

But there are those who are right now engaged in foreseeing the future that will come after the coronavirus recedes. A common place is the idea that the world will change after the epidemic, as it often happened in past centuries.

Outbreaks of deadly diseases certainly had a great impact on human communities, and it was not limited to discoveries and inventions in the field of medicine; epidemics influenced politics, economics, culture. Even the very word “plague” has become an artifact of political culture – people began to use it to stigmatize ideological opponents, calling the plague, for example, communist or fascist ideas. Thus, they were a priori given a negative assessment, because the plague is something in which, by definition, there can be nothing acceptable.

Alternate past

Epidemics also had a direct impact on the development of history. We do not know how events would have turned out later if Pericles, one of the founding fathers of Athenian democracy, had not died of the “Thucydides” plague during the Peloponnesian War in 429 BC. and if the plague had not taken to the grave of monarchs and pretenders to the throne in the Middle Ages. Already closer to our days – if US President Woodrow Wilson had not been ill with the Spanish flu during the Paris Peace Conference in 1919 and had not succumbed, due to the weakening of the body, to the demands of the French to secede from Germany in a number of areas, Germany might not have been seized after this by the spirit of revengewhich led to the disastrous World War II.

In Rus’, Moscow could not have risen, if the family of Simeon the Proud had not died, as a result of which his nephew Dmitry, later named Donskoy, had become prince, and if other cities had not been impoverished during the plague of 1347-53, while in Moscow a strong system of outposts had already been created then who helped organize the quarantine. It is believed that thanks to this, the capital of the Moscow principality managed to avoid a mass pestilence.

Not English, but a dialect of French could become a world language – only after the epidemics of the early XIV century, the English language, practically not used by the descendants of the Norman conquerors, was returned to the extinct cities by settlers from villages less affected by the plague.

It was precisely the proximity of the plague foci that Pope Paul III in the XNUMXth century explained the transfer of the meetings of the Council of Trent from Trident itself, in South Tyrol, to Bologna, closer to Rome. If not for this circumstance, Holy Roman Emperor Charles V would most likely have succeeded in insisting on reforms in the Catholic Church. However, on its territory, the papal throne defended its power, thereby finally formalizing the break between Catholics and Protestants, which, as you know, had the greatest consequences.

Deadly weapon

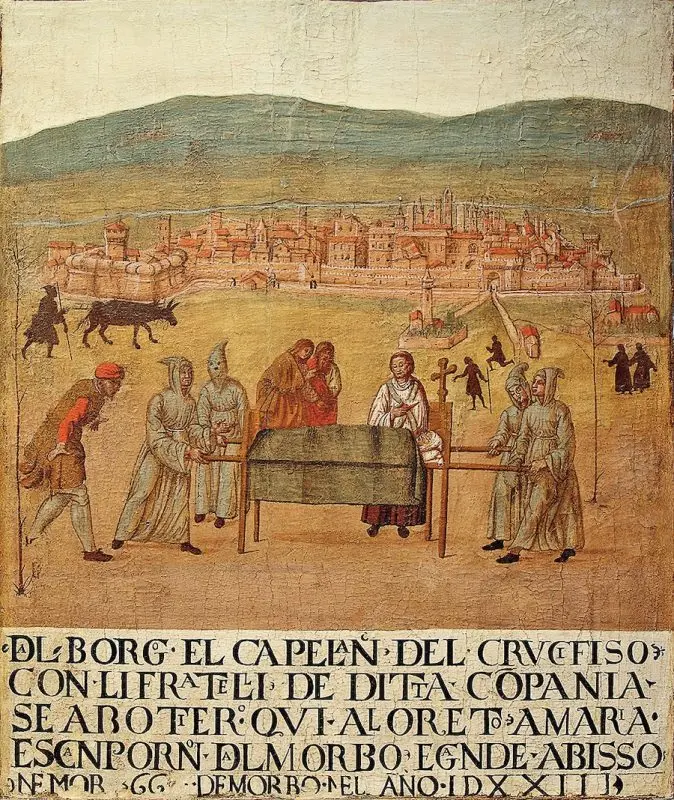

The plague may have found a “use”, so to speak, in military affairs: there is a legend that bacillus-infected corpses were thrown by throwing machines during the siege of cities and castles. In European historiography, this legend is known from the words of a certain Gabriel de Musset from Piacenza, who reported that this is how the Tatar army took Kaffa (Feodosia) in 1346:

“The city was strewn with mountains of the dead, and the Christians had nowhere to run and nowhere to hide from such a misfortune…”

Whether this was the direct cause of the plague entering Europe on the ships of the fleeing Genoese, modern scholars doubt. But it is nonetheless the first biological warfare documented in such detail, and most historians consider it plausible. By the way: the Tatars still failed to take Kaffa, and there are no other similar stories, but the mere thought of biological attacks still scares people.

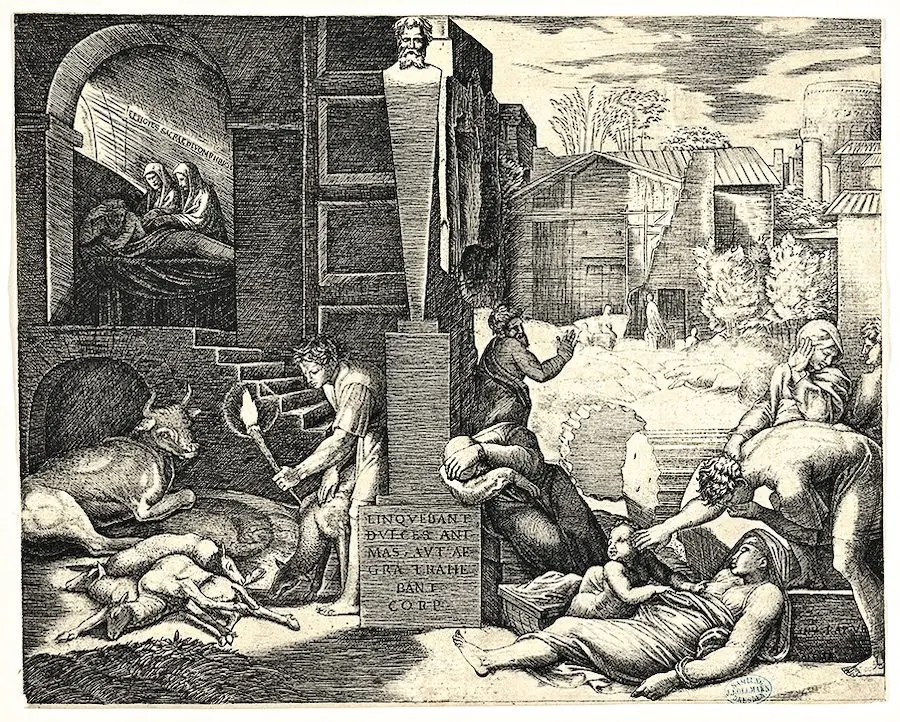

Diseases had a huge impact on the colonial processes of modern times. The natives of the Americas, Asia, Polynesia did not have immunity to diseases common to Europeans, since they did not have the same livestock as the Europeans – a carrier of infections. When, at the beginning of the 1525th century, black pox, brought to the Caribbean by Europeans, reached the state of the Incas, several hundred thousand people died rapidly, according to various estimates, including the supreme ruler Huayna Capac. His death in XNUMX also sparked a civil war between the heirs, and by the time Francisco Pizarro’s detachment arrived, the Incas were already significantly weakened and disoriented by losses from disease and war.

An epidemic of smallpox and then typhoid fever ended the multi-million Aztec civilization – their capital, Tenochtitlan, lost almost half of its population in 1520 alone. In a similar way, diseases affected the North American Indians and the population of the Pacific Islands: measles, influenza, smallpox led to extremely rapid depopulation of the natives and facilitated the conquest of new territories. At the end of the XNUMXth century, epidemics of cholera and typhus made Tunisia easy prey for the French.

By 1763, there is a well-known case of an attempt to deliberately infect the Ottawa Indians, who besieged Fort Pitt, with blankets from smallpox patients. As in the case of the siege of Kaffa, it is not known for certain whether this particular action caused the outbreak of the disease (smallpox occurred from time to time among Indian tribes), but Americans still remember these blankets.

Inoculation for discoveries

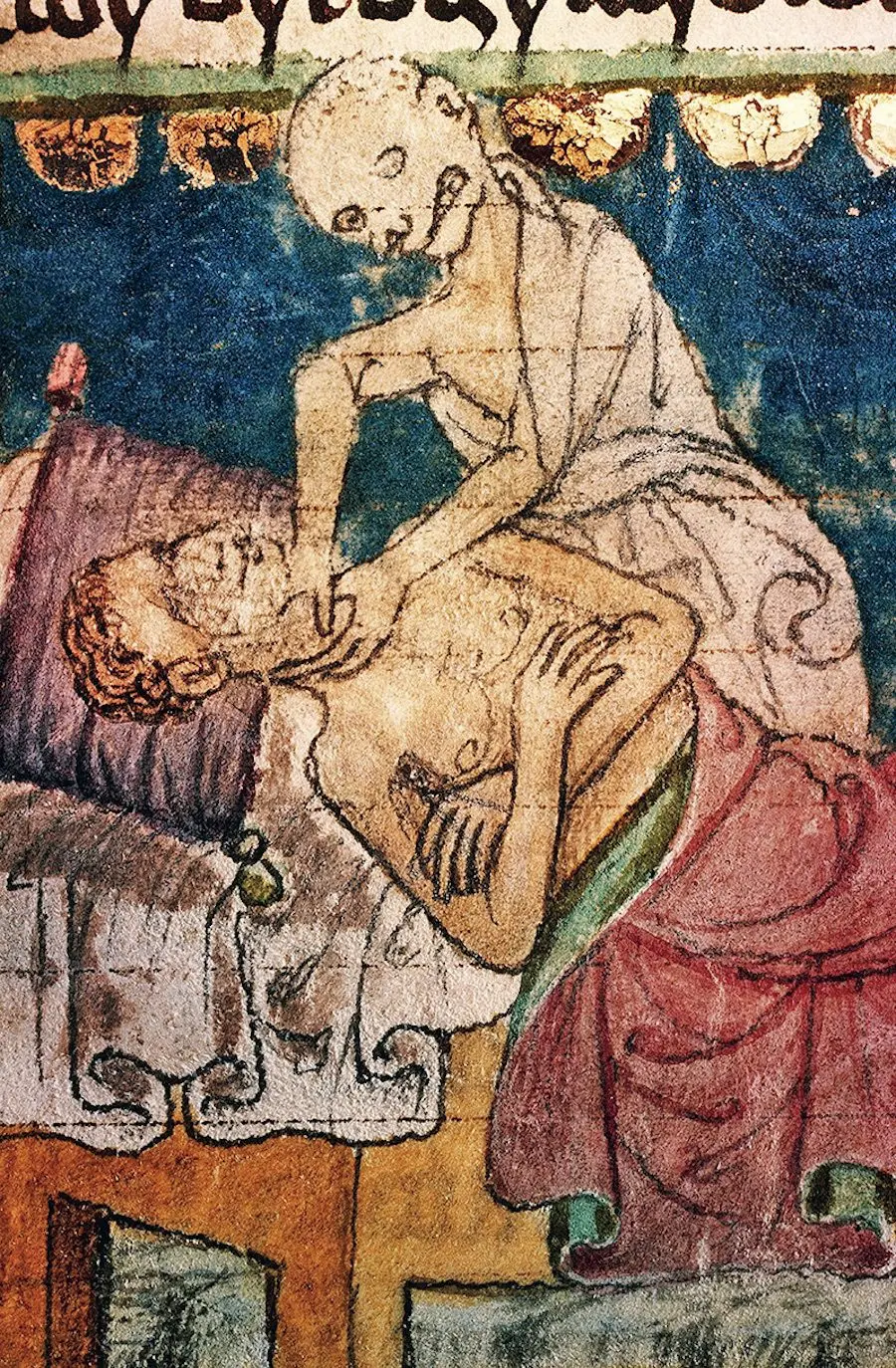

Having a situationally extremely negative effect, epidemics often led to consequences that we would rate rather as positive – what in English is called “silver lining” (silver lining). First of all, this, of course, is the development of medicine and hygiene. During outbreaks of plague in the XNUMXth-XNUMXth centuries, medical examinations at home appeared for the first time, the allocation of separate wards and hospitals for plague-infected patients, and quarantine for those arriving in the city. Subsequently, the fight against the disease led to the ideas of regular street cleaning, water purification, the establishment of permanent health services, and so on. It is important that it was secular medical institutions that began to develop, while before, taking care of the soul and body was mainly a church prerogative.

Thanks to an outbreak of malaria in the Vatican in 1623 (38 high hierarchs of the church died, Pope Urban VIII fell ill), we got quinine – the pope announced the search for a cure, and Jesuit missionaries found it in Peru. The drug from the bark of the cinchona tree was at first called the “powder of the Jesuits.” Quinine became a valuable product, and wars were fought for control of the territories where it was mined. By the way, Oliver Cromwell, who did not trust the Catholics, at one time refused to take quinine and in 1658 he died safely from malaria.

Smallpox later enriched medicine with the idea of mass vaccination. Although this principle itself was known to the ancient Chinese, it took centuries for Europeans to adopt it – but since 1853 in the UK, vaccinations were declared mandatory from three months.

Any epidemic up to the present day leads to the mobilization and improvement of health systems, the creation of new structures. In the 1930s, for example, after an outbreak of psittacosis (“parrot fever” spread from exotic birds), the hygiene laboratory in the United States, where scientists were looking for a vaccine, was transformed into the National Institutes of Health. A few years ago, after the Ebola epidemic, a similar institution appeared in Liberia.

Rebirth after pestilence

In England, during the outbreak of plague in 1348, up to a third of the population died out; a shortage of workers led to a rise in labor rates, and King Edward III issues the Ordinance on Workers and Servants, according to which workers were obliged to be hired for the same wage as before the plague, as well as artisans, merchants and keepers of taverns were forbidden to inflate prices , and the feudal lords – to pay more than usual.

In 500 years, Karl Marx will call this act the beginning of “exploitative” and “hostile to workers” legislation – hostile or not, but it became the first in a series of laws regulating the relationship of workers and employers. Already in 1351, the English statute “On Workers” described in detail who should be paid how much for what work, as well as the subtleties of hiring, and in general it can be said that it was the “Black Death” that laid the foundation for the formation of labor legislation. These laws were unpopular with the people, so for the same reasons the plague, it turns out, also became an economic prerequisite for the growth of class divisions, which led directly to Wat Tyler’s rebellion in 1381 and, in a historical perspective, to the development of socialist ideas. Similar processes took place in other European countries.

But the economic impact of the plague was not just about recruitment. Depopulation forcedly led to an increase in labor productivity and economic efficiency, increased the capital intensity of agriculture. Despite restrictive laws, the cost of labor still rose – even many landowners illegally paid workers extra money, bypassing royal regulations. Peasants began to change their place of residence more often in search of work, the cost of land fell. Caught in a hopeless situation, the lords conceded to farmers the right to dispose of land in exchange for rent, serfdom collapsed. It was replaced by mercantilism, the forerunner of the capitalist system.

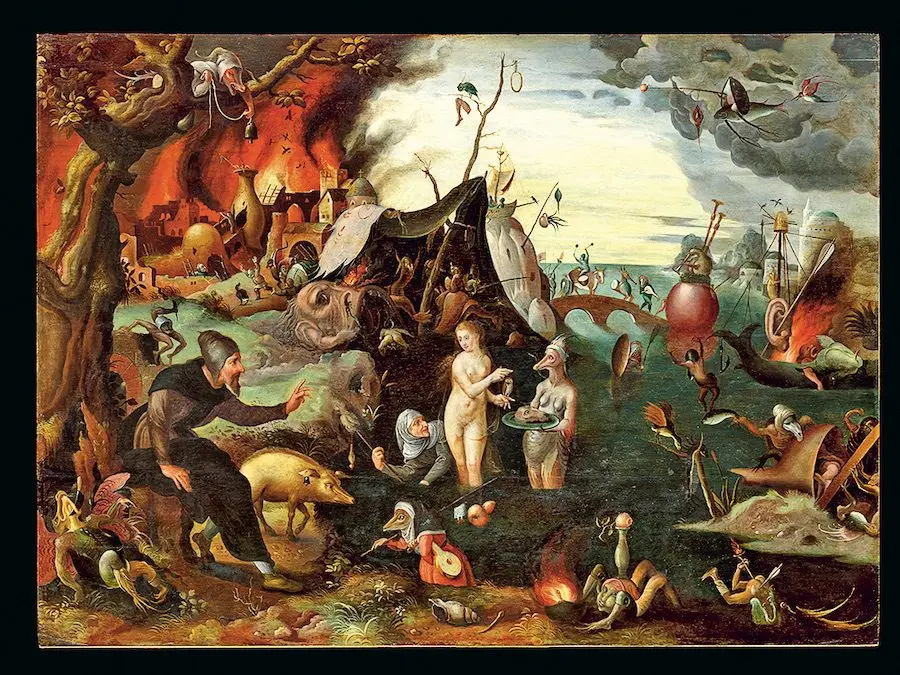

In other words, the world began to take on more or less familiar outlines. After the plague, a fall in inflation and an increase in consumption began to be observed. The redistribution of wealth in favor of the survivors led to the rise of a new aristocracy – the Medici family, for example, although rich before the plague, managed to become super-influential after half of Florence died out. The rich began to spend more on the arts, thereby bringing the Renaissance closer. In general, the horror experienced made people consume and spend more on pleasure – they realized how short life is. Trading has become more competitive, business strategies have become more flexible and require better risk management skills. Do not forget that the development of commerce was also strongly influenced by the Protestant ethics – which, as we remember, also appeared not without the participation of the plague.

Would the same thing have happened if not for the epidemics? How to know. More likely yes than no, but the processes in any case would take more time and would be embodied in a more moderate form, and maybe in some other way.

There is a lot of debate today about what impact the COVID-19 epidemic will have on the world. Many experts criticize capitalism for showing its weakness in the fight against the coronavirus. How exactly social relations and economic ties will change, what new habits and institutions they will lead to, is difficult to predict. But you can be sure that humanity, as always, will extract some positive from the epidemic.

Subscribe to the Trends Telegram channel and stay up to date with current trends and forecasts about the future of technology, economics, education and innovation.