Contents

Charles Dickens, the Founding Fathers of America, the pirates and sailors of the Royal Navy, they all enjoyed the punch. Born in the 17th century and endlessly supplemented with new ingredients, it has long gone beyond its original four or five-piece form and has become one of the most powerful categories of mixed drinks. In this resource, you will learn how to make 5 classic punches and discover the true balance of it.

A long time ago we told you how to make 7 perfect warming punches for a cold winter. These were predominantly European, modern mulled wines based on wine (except, perhaps, Charles Dickens’ punch, which can be safely considered Old Testament and most historical). Now it’s time to tell you about the classic punch, which for centuries saved brave sailors from scurvy, and the European aristocracy from melancholy.

“This ancient cup is mine – it conveys to us

The noise and laughter of past revels, Christmas chimes.

A lot of honest and direct funny daredevils

They drank punch in a circle when the goblet was new.

Thus begins the punch chapter in Harry Craddock’s The Savoy Cocktail Book. Then Craddock continues with a very important and, perhaps, the most important advice: “… there is one great secret in its preparation, which must be mastered with patience and care. It consists in the fact that the various subtle ingredients must be mixed in such a way that neither bitterness, nor sweetness, nor alcohol, nor one ingredient stands out above the others.

The classic punch proportions are easy to remember thanks to the rhyme: “One of Sour, Two of Sweet, Three of Strong, Four of Weak.” This is a recipe for the traditional Bajan ‘Barbadian’ rum punch.

It is interpreted like this:

- One of Sour (one of the acidic ones) = lime juice or lemon juice

- Two of Sweet (two of sweet) = sugar

- Three of Strong (three of the strong ones) = arak, rum or other alcohol

- Four of Weak (four of the weak) = water, fruit juice, tea, etc.

Those who adhere to the “five-part” component of the cocktail also single out spices separately: nutmeg, cinnamon, rose water, etc.

It is widely believed that the drink got its name from the Hindi word for “five”, according to the number of ingredients that it originally included: lemon or lime juice, sugar, alcohol (rum, brandy or arak), water and spices (nutmeg) . David Wondrich, cocktail expert and author of Punch: The Delights (and Dangers) of the Flowing Bowl, a book dedicated exclusively to the drink we are researching, disagrees with most. In his opinion, the word “punch” comes from the name of the huge, 500-liter barrels of punch (puncheon), which are still used in the rum industry to this day (American oak punches from rum are often used for aging sherry in them, and barrels from Spanish oak for the production of sherry are in great demand in distilleries).

The virtues of rhyming punch are appreciated all over the world, but few people make it according to this formula. As Wondrich said, “To me, making punch is like barbecuing. It’s a thing… well, you don’t need a prescription; it’s a process. You can mix it with a little bit of this, a little bit of that, it’s all instinct, no science.”

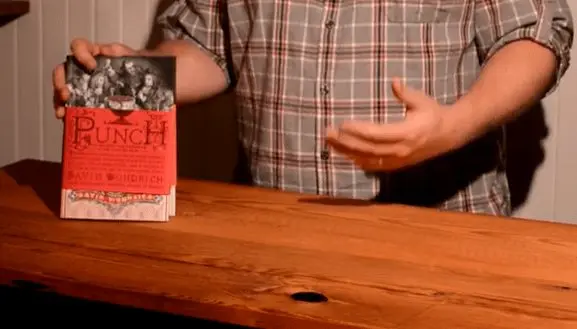

David Wondrich and his punch

David, of course, is a great expert and deserves absolute trust in the field of mixed drinks, but having at least some kind of recipe still brings clarity and adds some confidence on the path of a novice mixologist. The recipe below is very easy to follow, quite balanced and can serve as a starting point into the endlessly varied world of punches.

Classic rum punch

A traditional five-part rum-based punch in the Barbadian style. The recipe is adapted from various sources specifically for Rum Diary.ru.

A type cocktail, punch

Kitchen english

Prepare 8 hours 10 minutes

Cooking 30 minutes

Охлаждение 15 minutes

Total 8 hours 55 minutes

Portions 24 servings of 90 ml

Ingredients

- 4 bright yellow lemons

- 150-170 г granulated sugar

- 180 ml strained lemon juice

- 750 ml Jamaican rum

- 1 л water (or tea)

- 1/3 nutmeg

Instructions

24 hours before serving the punch:

Prepare a punch bowl or any other suitable container with a capacity of at least 4 liters. Find or buy a suitable bucket for mixing and pouring the finished drink.

Fill a silicone bread pan or other suitable container with water and place in the freezer to make a large block of ice the size of the bowl.

Remove the zest from 4 non-waxed lemons, trying to minimally touch the white subskin (albedo), and place it in a liter jar.

Using a measuring cup, measure out 180 ml of granulated sugar (or weigh 150-170 g of sugar) and pour it into a jar to the zest.

Close the jar tightly and shake well, then leave overnight to prepare the real “oleo-sugar”.

Immediately before serving:

Add 180 ml of freshly squeezed, strained lemon juice to a jar of “oleo-sugar”. Close the jar again and shake well until all the sugar has dissolved. Pour the resulting syrup into a punch bowl.

There also send a 750-milliliter bottle of fragrant Jamaican rum and 1 liter of cold water.

Remove the previously frozen block of ice and carefully place it in the bowl. In this form, it should stand for 15 minutes in a cool place.

Grate a third of the nutmeg on top of the punch, and then, using a ladle, mix. You can drink!

Field notes

“Oleo-saccharum” (Oleo-saccharum – from lat. Butter sugar) – a syrup obtained due to the hygroscopic properties of sugar, due to which aromatic oils are extracted from the peel of citrus fruits, mainly lemons. For punch, “oleo-saccharum” is like a soup broth and has been its indispensable ingredient almost since the appearance of the cocktail. Citrus oils add complexity to the flavor of the sour juice and also “dry” the punch, helping to balance the sugar and other expressive ingredients.

Cooking it is very simple: you need to grind the citrus zest with sugar (you need to take about 1-40 g of sugar for the zest of 45 lemon) and leave overnight at room temperature. After that, in order to dissolve all the sugar, you need to add as much lemon juice to the zest as the volume of sugar was used. Wondrich advises leaving the zest with sugar for 3-4 hours (but not more than 8 hours) on a sunny windowsill. This saves time, and the result is even more rich and fragrant.

Oops, I forgot to make the “oleo sugar”

If you don’t have time to make lemon syrup, skip the first 5 steps and instead dissolve 180 ml of cane sugar in 90 ml of water over low heat. Let the syrup cool for 10 minutes and then proceed to step 6 using it as “oleo sugar”, but lime juice is preferred instead of lemon juice. The replacement, of course, is not equivalent, but it turns out delicious (in any case, acceptable).

Add some funk

The first punches were prepared on the basis of Batavia-arak, the Indonesian great-grandfather of Roma. It, as well as many other sugarcane distillates, has notes that are commonly referred to as “funk”. They are related to the aromas and flavors of black banana and caramelized pineapple, and are also present in meat when left to ripen for a while. Such tastes are also called “hogo” (hogo), an anglicization of the French term “Haut Goût” (high taste).

In some rums, “funk” can be overpowering and not very pleasant to drink just like that, but in classic punches, they transform into something really tasty. You want to drink such a cocktail again and again. In general, add some “funk” to your punch and you will be happy. To do this, take any very expressive Jamaican rum or, if you’re lucky, a bottle of Batavia-arak from Java – no thin Bacardi!

Replace water with tea

Punch originated in that part of the world where the English were beginning to get involved in tea. Not surprisingly, tea is part of most of his early recipes and continues to shape new ones. Only now it’s not just black and green. Huge variety of Chinese tea flavors (drooling at the thought of a punch where “4 parts weak” would be taken from thinly brewed red kidney tea or well-roasted oolong teas like Da Hong Pao), hibiscus, flower teas, herbal infusions… Why add just water when there is such a wonderful and infinitely variable, delicious diluent?

By the way, about dilution

When it comes to your punch and its dilution, you have to make a decision. Are you going to start with the perfect strength for the drink and maintain it by keeping the punch chilled by means other than direct contact with ice, or are you going to let your punch develop?

If you are not making a punch that will be drunk immediately after serving, then regular ice cubes are not suitable, because the ice will melt quickly and dilute the cocktail greatly. Use a large block of ice instead. The larger the punch bowl, the larger the piece should be. Preparing a really huge piece of ice is very simple – freeze water in a silicone mold for bread or cake (and you can also throw in different berries and fruits, aesthetic ecstasy is guaranteed).

If you need to keep a punch of one strength for a long time, for example, if you serve it to guests as a welcome drink at a bar, simply pour it into bottles without ice and store it in the refrigerator. Just remember to dilute it to the desired strength. The ideal level of alcohol content in punches is considered to be 16-20%, the strength of sherry.

When the basics of classic punching are mastered, try cooking something more complicated. For inspiration, we leave here four historical recipes that have appeared so long ago that they deserve the right to be called traditional. One of the best such drinks is definitely…

Philadelphia Fish House Punch

In Imbibe! David Wondrich wrote (a free translation by an author new to the original language): “Philadelphia Fish House Punch deserves legal protection, education in schools, and should be on every table during the Fourth of July celebrations.” This recipe was invented by a group of rebellious colonial Americans—fishermen, politicians, and similar Philadelphians—who founded the Schuylkill Fishing Company of Pennsylvania, also known as the State in Schuylkill, in 4. The members of the club actually declared themselves a sovereign state and continue to stick to this line to this day.

Heady and heavy, Philadelphia Fish House Punch is meant for lazy summer afternoons (or – if warmed up like mulled wine – lazy winter weekends), so we don’t recommend pairing it with any plans, fishing or anything else.

Philadelphia Fish House Punch

- 200 g sugar

- 4 medium lemons

- 1 liter black tea or water

- 250 ml lemon juice

- 1 liter of Jamaican rum

- 500 ml of cognac

- 250 ml peach brandy

How to cook:

Grind sugar with lemon zest without white albedo directly in the punch bowl (quick “oleo-sugar”), let it brew for 30 minutes. Add warm tea or water, stir until sugar dissolves. Add rum, cognac, lemon juice and peach brandy. Mix. Place a large block of ice in a bowl, sprinkle with freshly ground nutmeg and garnish with lemon wedges. Can be poured into glasses using the ceremonial ladle.

Punch Daniel Webster

The legendary punch, the recipe for which Wondrich unearthed in Steward & Barkeeper’s Manual, 1869. Its author is the notorious politician, senator, member of the House of Representatives and US Secretary of State, Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852). There are a lot of recipes for Webster’s punch on the Web, but this one is considered authentic – Webster allegedly gave it to his friend, “Major Brooks from Boston”, while on his deathbed (poetic as always). In any case, this is a very revealing recipe from the middle of the 19th century and has always been considered a classic.

Daniel Webster’s Punch

- 3 medium lemons

- 100 g sugar

- 1 black tea bag

- 500 ml of water

- 120 ml lemon juice

- 180 ml of cognac

- 180 ml dry Oloroso sherry

- 180 ml of Jamaican rum

- 350 ml rich bordeaux red wine

- champagne on demand

Remove the zest from the lemons without white albedo and grind in a punch bowl with sugar, wait 20 minutes. Brew a tea bag in 0,5 liters of boiling water for 5 minutes, cool. Add tea, lemon juice, cognac, sherry, rum and red wine to the bowl, mix thoroughly. Strain the punch from the lemon zest and refrigerate for at least 30 minutes. 15 minutes before serving, put an ice ring in the bowl*. Pour the finished cocktail into glasses and add a little sparkling wine to each.

*ice ring: Pour water into the cake pan, filling it halfway. Evenly distribute 5 strawberries cut lengthwise, 5 pineapple slices and 10 mint leaves around the circle. Freeze overnight.

Punch Hanna Woolley

The punch recipe by Hannah Woolley, the famous English writer, was first published in 1672, making it a truly old-fashioned punch and one of the first recipes to be written down on paper. This is his interpretation, with the addition of the rare aperitif Barolo Chinato. Barolo Quinato is a fortified red wine from Piedmont, a type of vermouth with the addition of cinchona bark and up to 40 other herbal ingredients (that is, it can be replaced with regular vermouth and some bitter bitter).

Hannah Wooley Punch

- 300 ml of cognac

- 250 ml Barolo Quinato wine

- 300 ml nutmeg syrup*

- 750 ml dry red wine

- 300 ml lemon juice

- about 150 ml soda

Combine the first five ingredients in a punch bowl and top up with soda. Garnish with redcurrant or cranberry sprigs, edible flowers, grated nutmeg and orange slices. Serve in glasses with ice.

*nutmeg syrup: mix 1 liter of water, 900 g of sugar and 1 grated whole nutmeg in a saucepan, heat, stirring, until the sugar is completely dissolved.

Regent’s punch

According to Wondrich, it was punched by George Augustus Frederick, Prince Regent of England from 1811 to 1820, and later by King George IV. He was still a reveler and an egoist, but it was this drink, according to an eyewitness, that made him a tolerable person.

Regent Punch

- 4 medium lemons

- 500 ml black or green tea

- 300 grams of powdered sugar

- 180 ml lemon juice

- 350 ml orange juice

- 250 ml of pineapple juice

- 500 ml brandy

- 250 ml dark rum

- 2 bottles of brut champagne

- orange rings

- pineapple wedges

Prepare a standard “oleo-sugar” directly in the punch bowl, wait 20-30 minutes. Add cooled tea, juices and alcohol. Mix. Add two to three large ice cubes and champagne just before serving. Decorate the punch with orange and pineapple.

The history of the punch

Who and when made the first punch is not known for certain, but most historians, including Wondrich, agree that it was a Briton.

The first known written mention of punch dates back to September 28, 1632 (a letter from Robert Addams, a British employee in the East India Company). The first documented recipe, however, did not appear until 1638, when the German adventurer Johan Albert de Mandelso, manager of a factory in Surat, India, recorded that the workers there prepared “a peculiar drink consisting of alcohol, rose water, citrus juice and sugar.”

Of course, trade routes had a great influence on the popularization of the new drink. Tea and citrus came from Southeast Asia, as did the then progenitor of most distilled drinks, arrack, which was made from a variety of raw materials (including palm wine or, in the case of Batavia-arrack from Java, molasses and rice). Arak was the preferred punch ingredient in Europe throughout the 17th and 18th centuries. In Sweden, it is still popular today.

British sailors brought punch to Europe

Punch helped sailors survive long sea passages – citrus fruits saved from scurvy, alcohol – from homesickness. When they returned to the ports of London, they always brought with them arak and other punch ingredients from the East Indies. Then it was fashionable to visit the docks and drink a bowl of punch with sailors.

In the mid-1600s, after the Stuart Restoration, punch based on East Indian arrack and later West Indian rum became a fashionable social drink in London coffeehouses and other drinking establishments. For their owners, punch was a very profitable commodity because it was not taxed – it was so new that it was outside the tax system.

The drink remained a popular choice for the English aristocracy for hundreds of years. The spirits used, tea, sugar, citrus fruits and nutmeg were expensive ingredients that only wealthy people could afford. In the 1690s, a 3-liter bowl of punch cost as much as a week and a half of the living wage. Punch bowls have become an item of luxury and ostentation. In the 18th century, every self-respecting gentleman always carried with him a small silver grater and nutmeg to rub over his punch at any time.

Punch and rum

As soon as Britain colonized cane sugar countries, the Royal Navy quickly replaced the daily allowance of a gallon of beer or a pint of wine with half a pint of Jamaican rum. Rum did not spoil on long trips and took up much less space on board. Somewhere it was kneaded into punch, and somewhere grog was prepared.

In the tropics, as Jeff Berry wrote in the preface to Beachbum Berry’s Potions of the Caribbean, “Rum mixed with sugar and lime made the nasty, rough and short life of an ordinary Caribbean fighter a worthy life.” Indeed, 17th and 18th century sea hooligans preferred a punch bowl over drinking fetid rum straight from the bottle.

There is an eyewitness account dated 1688, who claims that over a punch bowl an agreement (letter of marque) was signed between the infamous pirate William Kidd and the commander-in-chief of the Caribbean fleet of England. The punch was allegedly made with “rum, water, lime juice, egg yolks, sugar, and a little nutmeg on top”.

Evolution, oblivion, renaissance

With the spread of punch, from around 1670, recipes began to appear calling for alternative (often cheaper) spirits, notably brandy in Europe and rum in America. Later, more luxurious recipes were invented, where the alcohol base became multi-component, and red wine and champagne often appeared among the traditional ingredients.

Despite the increased strength of the then punches, it was common for large companies to empty a dozen bowls of drink in one sitting. At the height of the cocktail’s popularity, in 1783, the governor of New York, George Clinton, greeted the French ambassador with 30 bowls of rum punch for only 120 guests (and another 135 bottles of Madeira, 36 ports and 60 beers). Wondrich writes that at a similar feast in 1785, a group of 80 people drank 30 bowls of punch—plus another 44 at a dinner—celebrating the election of a New England minister.

But, starting in the mid-19th century, a series of gradual changes in society began to push punches out of everyday life. On the one hand, the improvement of distillation processes and the advent of aged spirits removed the need for flavoring low-quality rum with citrus and spices. The industrial era in America, where punches were among the first to disappear, added a sense of urgency to all activities, including drinking. The practice of making punch, which often included a long period of waiting for the “oleo-sugar” to be just right, became a matter of celebration and ceremony rather than a daily ritual.

Now the world is experiencing a second punch renaissance and the drink is back in fashion. Currently, it is prepared in the leading bars of the world. For example, at New York’s Dead Rabbit, the world’s best bar of 2016, punch is the welcome drink for every guest. And the Punch Room in London serves nothing but punch, almost certainly the world’s first punch bar since the mid-1800s. So it goes.