Contents

The answer to the constant question about the smallest thing in the universe has evolved along with humanity. People once thought that grains of sand were the building blocks of what we see around us.

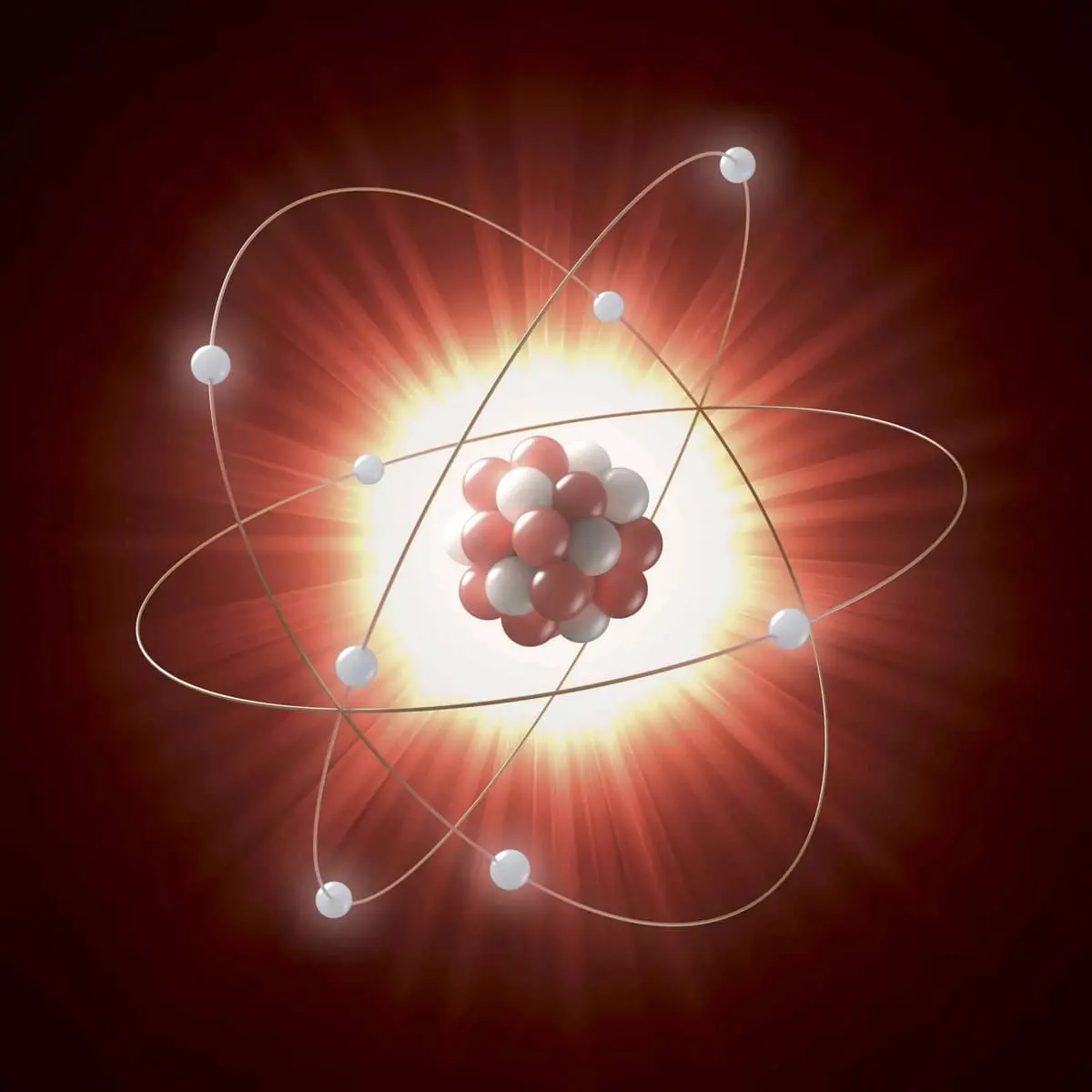

Then the atom was discovered. The concept of atoms was first proposed by the Greeks, who believed that objects could be infinitely divided into two parts until one indivisible particle of matter remained. This unimaginably small unit could not be divided further and was therefore called “atom”, derived from the Greek word A-tomes. Where A means “not” и “Tomos” – share.

It was thought to be indivisible until it split open to reveal the protons, neutrons, and electrons within. They, too, seemed to be fundamental particles before scientists discovered that protons and neutrons were made up of three quarks each.

So which of the particles are the smallest in the universe?

10 Electronic

Electronic is a negatively charged subatomic particle. It can be free (not bound to any atom) or bound to the nucleus of an atom. Electrons in atoms exist in spherical shells of various radii representing energy levels. The larger the spherical shell, the higher the energy contained in the electron of electrical conductors, the current flow arises as a result of the movement of electrons from atom to atom separately and from negative to positive electric poles as a whole. In semiconductor materials, current also occurs as the movement of electrons.

Electronic is a negatively charged subatomic particle. It can be free (not bound to any atom) or bound to the nucleus of an atom. Electrons in atoms exist in spherical shells of various radii representing energy levels. The larger the spherical shell, the higher the energy contained in the electron of electrical conductors, the current flow arises as a result of the movement of electrons from atom to atom separately and from negative to positive electric poles as a whole. In semiconductor materials, current also occurs as the movement of electrons.

9. Positron

Positrons are the antiparticles of electrons. The main difference from electrons is their positive charge. Positrons are formed during the decay of nuclides, in the nucleus of which there is an excess of protons compared to the number of neurons, when decay occurs, these radionuclides emit a positron and a neutrino.

Positrons are the antiparticles of electrons. The main difference from electrons is their positive charge. Positrons are formed during the decay of nuclides, in the nucleus of which there is an excess of protons compared to the number of neurons, when decay occurs, these radionuclides emit a positron and a neutrino.

While the neutrino comes out without interacting with the surrounding matter, the positron interacts with the electron. During this process of annihilation, the masses of the positron and electron are converted into two photons that diverge in almost opposite directions.

8. Proton

Proton stable subatomic particle with a positive charge equal in magnitude to the unit charge of an electron and a rest mass of 1,67262 × 10 -27 kg.

Proton stable subatomic particle with a positive charge equal in magnitude to the unit charge of an electron and a rest mass of 1,67262 × 10 -27 kg.

About a decade ago, both spectroscopy and scattering experiments seemed to converge at a proton radius of 0,8768 femtometers (millionths of a millionth of a millimeter).

But in 2010, a new turn in spectroscopy cast doubt on this idyllic consensus. The team measured a proton radius of 0,84184 femtometers.

7. Neutron

Do you know that neutrons are in the nucleus of an atom. Under normal conditions, protons and neutrons stick together in the nucleus. During radioactive decay, they can be knocked out of there. Neutron numbers are able to change the mass of atoms because they weigh about the same as a proton and an electron together.

Do you know that neutrons are in the nucleus of an atom. Under normal conditions, protons and neutrons stick together in the nucleus. During radioactive decay, they can be knocked out of there. Neutron numbers are able to change the mass of atoms because they weigh about the same as a proton and an electron together.

Neutrons can be found in almost all atoms along with protons and electrons. Hydrogen -1 is the only exception. Atoms with the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons are called isotopes of the same element.

The number of neutrons in an atom does not affect its chemical properties. However, this affects its half-life, a measure of its stability. An unstable isotope has a short half-life, in which half of it decays into lighter elements.

6. Foton

Imagine a beam of yellow sunlight shining through a window. According to quantum physics, this beam is made up of billions of tiny packets of light, called photons, that flow through the air. But what is photon?

Imagine a beam of yellow sunlight shining through a window. According to quantum physics, this beam is made up of billions of tiny packets of light, called photons, that flow through the air. But what is photon?

A photon is the smallest discrete quantity or quantum of electromagnetic radiation. It is the basic unit of the whole world.

Photons are always in motion and in vacuum move at a constant speed to all observers 2,998 × 10 8 m/s. This is usually called the speed of light, denoted by the letter c.

According to Einstein’s quantum theory of light, photons have an energy equal to the frequency of their oscillations multiplied by Planck’s constant. Einstein proved that light is a stream of photons, the energy of these photons is the height of their oscillation frequency, and the intensity of light corresponds to the number of photons.

5. Quark

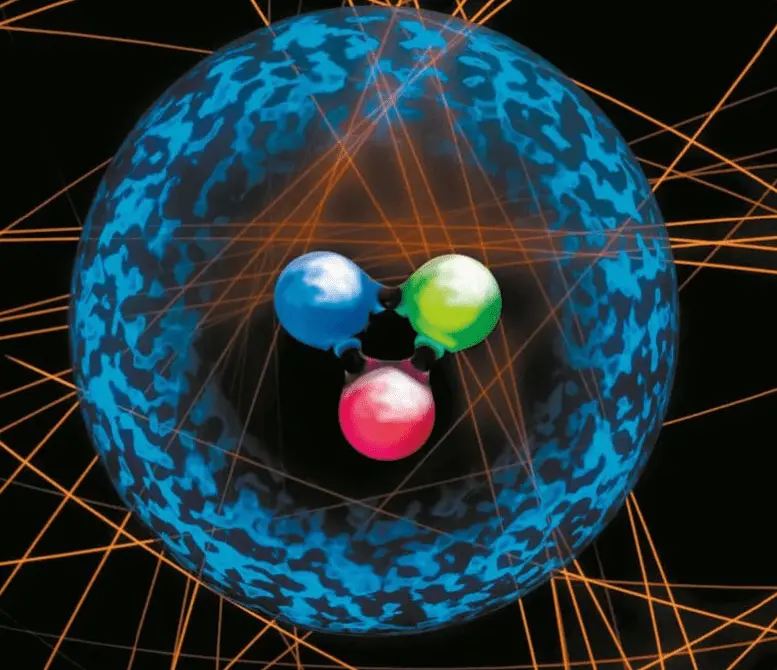

Quark is one of the fundamental particles in physics. They combine to form hadrons, such as protons and neutrons, which are the components of the nuclei of atoms.

Quark is one of the fundamental particles in physics. They combine to form hadrons, such as protons and neutrons, which are the components of the nuclei of atoms.

The quark is constrained, which means that quarks are not observed independently, but always in combination with other quarks. This makes it impossible to directly measure the properties (mass, spin, and parity); these traits must be inferred from the particles that are composed of them.

4. Gluon

A millionth of a second after the Big Bang, the universe was incredibly dense plasma, so hot that no nuclei or even nuclear particles could exist.

A millionth of a second after the Big Bang, the universe was incredibly dense plasma, so hot that no nuclei or even nuclear particles could exist.

The plasma was made up of quarks, the particles that make up nucleons and some other elementary particles, and gluons, massless particles that “carry” force between quarks.

Gluons are exchange particles for the color force between quarks, analogous to the exchange of photons in the electromagnetic force between two charged particles. The gluon can be considered the fundamental exchange particle underlying the strong interaction between protons and neutrons in the nucleus.

3. Muon

of muons have the same negative charge as electrons, but 200 times their mass. They are created when high-energy particles called cosmic rays slam into atoms in the Earth’s atmosphere.

of muons have the same negative charge as electrons, but 200 times their mass. They are created when high-energy particles called cosmic rays slam into atoms in the Earth’s atmosphere.

Traveling at a speed close to the speed of light, muons shower the Earth from all sides. Each hand-sized region of the planet is struck by about one muon per second, and the particles can travel through hundreds of meters of solid material before being absorbed.

According to Christine Carloganu, a physicist at the Clermont-Ferrand Physics Laboratory in France, their omnipresence and penetrating power make muons ideal for imaging large, dense objects without damaging them.

2. Neutrino

Neutrino is a subatomic particle that is very similar to an electron, but has no electric charge and very little mass, which may even be zero.

Neutrino is a subatomic particle that is very similar to an electron, but has no electric charge and very little mass, which may even be zero.

Neutrinos are one of the most common particles in the universe. However, because they interact very little with matter, they are incredibly difficult to detect.

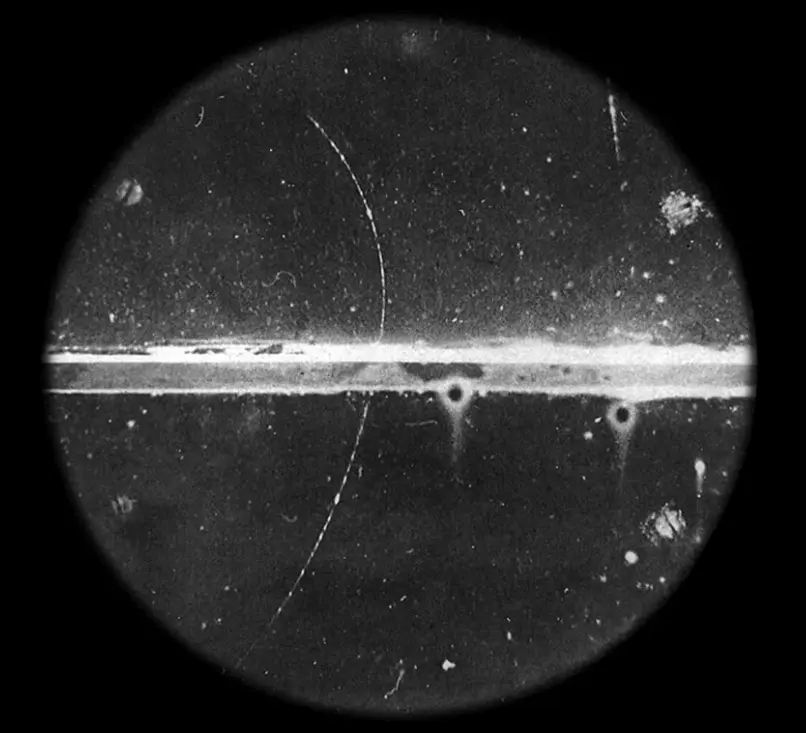

Neutrino detection requires very large and very sensitive detectors. Typically, low-energy neutrinos travel through many light-years of normal matter before interacting with anything.

Consequently, all ground-based neutrino experiments are based on measuring the tiny fraction of neutrinos that interact in reasonably sized detectors.

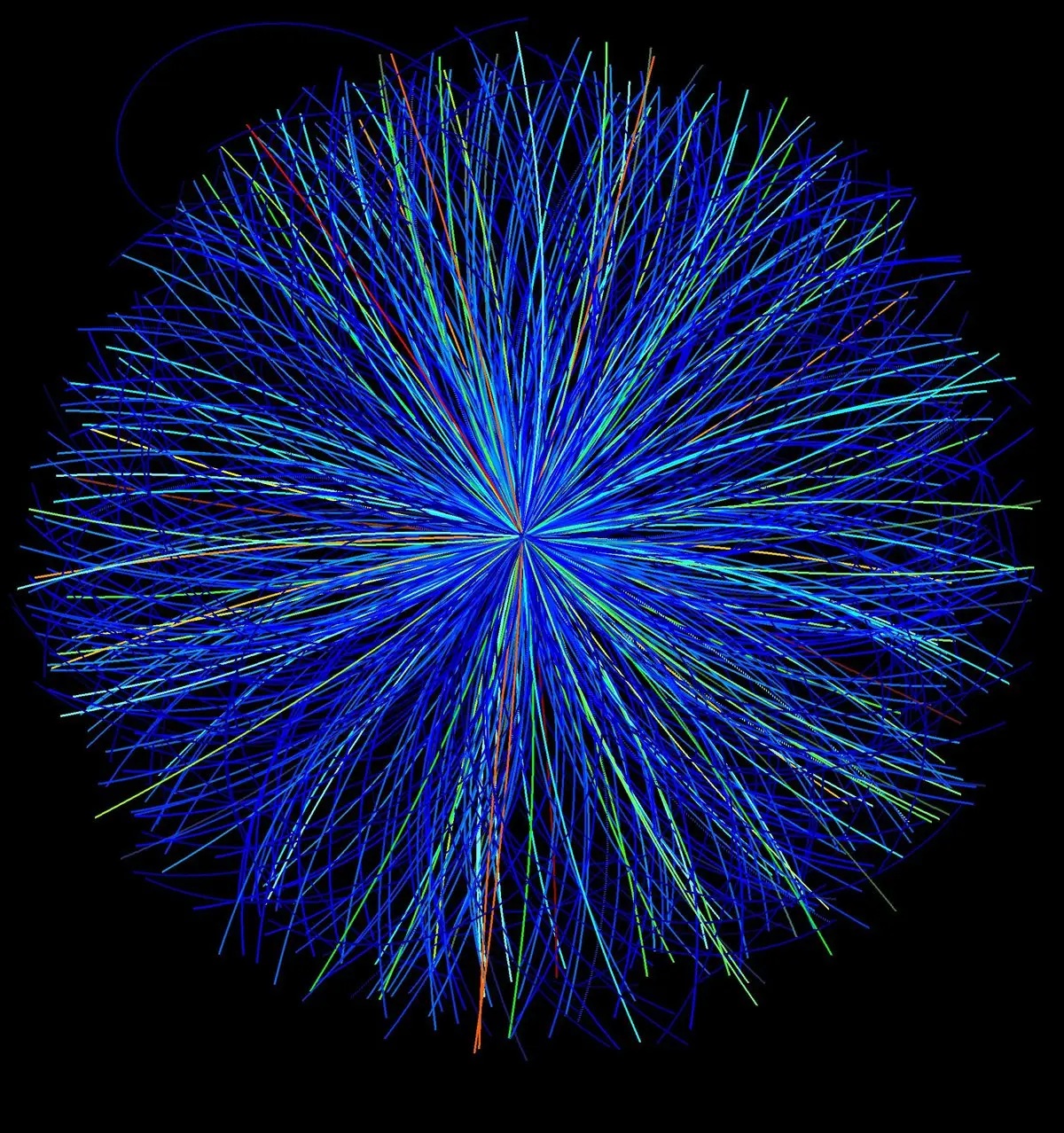

1. Higgs boson

Particle physics usually has a hard time competing with politics and celebrity gossip for headlines, but Higgs boson attracted serious attention. Possibly the famous and ambiguous nickname for the famous boson, “Particle of God”, made the media buzz.

Particle physics usually has a hard time competing with politics and celebrity gossip for headlines, but Higgs boson attracted serious attention. Possibly the famous and ambiguous nickname for the famous boson, “Particle of God”, made the media buzz.

On the other hand, the intriguing possibility that the Higgs boson is responsible for all the mass in the universe captures the imagination.

The Higgs boson is, if not the most expensive particle of all time. This is a bit of an unfair comparison; for example, the discovery of the electron took little more than a vacuum tube and real genius, and the search for the Higgs boson required the creation of experimental energies rarely seen before on planet Earth.