Adam Arnesson, 27, is no ordinary milk producer. First, he has no livestock. Secondly, he owns a field of oats, from which his “milk” is obtained. Last year, all those oats went to feed the cows, sheep and pigs that Adam raised on his organic farm in Örebro, a city in central Sweden.

With the support of the Swedish oat milk company Oatly, Arnesson began to move away from animal husbandry. While it still provides the majority of the farm’s income as Adam works in partnership with his parents, he wants to reverse that and make his life’s work humane.

“It would be natural for us to increase the number of livestock, but I don’t want to have a factory,” he says. “The number of animals must be correct because I want to know each of these animals.”

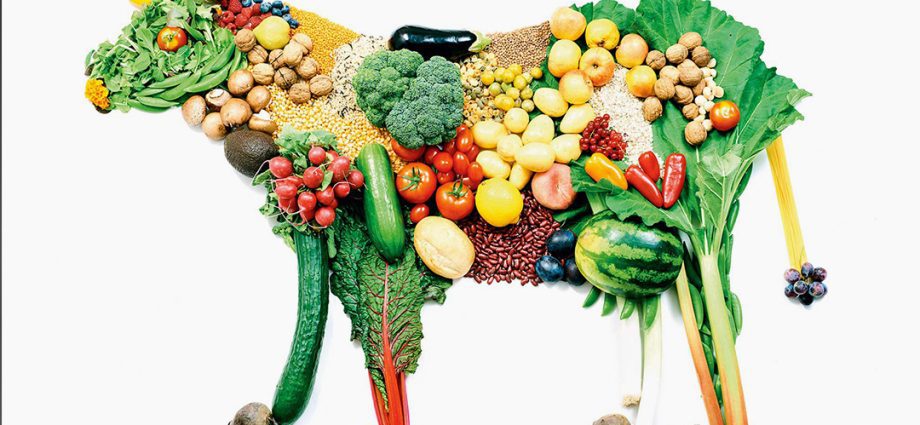

Instead, Arnesson wants to grow more crops like oats and sell them for human consumption rather than feeding livestock for meat and dairy.

Livestock and meat production account for 14,5% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Along with this, the livestock sector is also the largest source of methane (from cattle) and nitrous oxide emissions (from fertilizers and manure). These emissions are the two most powerful greenhouse gases. According to current trends, by 2050, humans will grow more crops to feed animals directly, rather than humans themselves. Even small shifts towards growing crops for people will lead to a significant increase in food availability.

One company that is taking active steps to address this issue is Oatly. Its activities have caused great controversy and have even been the subject of lawsuits by a Swedish dairy company in connection with its attacks on the dairy industry and related air emissions.

Oatly CEO Tony Patersson says they’re just bringing the scientific evidence to the people to eat plant-based foods. The Swedish Food Agency warns that people are consuming too much dairy, causing methane emissions from cows.

Arnesson says many farmers in Sweden see Oatly’s actions as demonizing. Adam contacted the company in 2015 to see if they could help him get out of the dairy business and take the business the other way.

“I had a lot of social media fights with other farmers because I think Oatly can provide the best opportunities for our industry,” he says.

Oatly responded immediately to the farmer’s request. The company buys oats from wholesalers because it doesn’t have the capacity to buy a mill and process grain, but Arnesson was an opportunity to help livestock farmers transition to the side of humanity. By the end of 2016, Arnesson had his own organic range of Oatly branded oat milk.

“A lot of the farmers hated us,” says Cecilia Schölholm, head of communications at Oatly. “But we want to be a catalyst. We can help farmers move from cruelty to plant-based production.”

Arnesson admits that he has faced little hostility from his neighbors for his collaboration with Oatly.

“It’s amazing, but other dairy farmers were in my shop. And they liked oat milk! One said he liked cow’s milk and oats. It’s a Swedish theme – eat oats. The anger is not as strong as it seems on Facebook.”

After the first year of oat milk production, researchers at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences found that Arnesson’s farm produced twice as many calories for human consumption per hectare and reduced the climate impact of every calorie.

Now Adam Arnesson admits that growing oats for milk is only viable because of Oatly’s support, but he hopes that will change as the company grows. The company produced 2016 million liters of oat milk in 28 and plans to increase this to 2020 million by 100.

“I want to be proud that the farmer is involved in changing the world and saving the planet,” says Adam.